Hidden Money Rules the System Doesn’t Want You to Know

This article unpacks the hidden financial rules that quietly shape wealth, from central banking and inflation to elite tax strategies, debt, and ownership. It shows how the system is structured and how individuals can reposition themselves on the winning side.

Introduction

During times of crisis, the rich seem to get richer while everyone else struggles. For example, in the recent global pandemic, billionaire wealth surged dramatically even as millions lost jobs and incomes. All that money didn’t vanish – it flowed upward into fewer hands. This isn’t mere coincidence or “bad luck” for the rest of us. It happens because those at the top understand hidden money rules that most people have never been taught. The financial system quietly runs on these unwritten rules, ensuring that wealth accumulates for the few who know how to use them.

Many people suspect the system is rigged, but they aren’t sure how. You work hard, save diligently, and follow the advice you’ve been given, yet true financial security remains out of reach. Meanwhile, a small elite plays a different game entirely – one with inside knowledge of money’s secrets. To level the playing field, we need to expose those secrets. From the inner workings of central banking and inflation to the strategies elites use to preserve and grow wealth, understanding these concepts is crucial. This is especially true in volatile markets around the world, including African economies like Kenya and Nigeria, where the stakes of not knowing the rules can be even higher.

In this comprehensive exploration, we’ll uncover the hidden money rules the system doesn’t want you to know. These range from global financial mechanisms down to personal wealth habits. By the end, you’ll see how decisions made in boardrooms and central banks trickle down to affect your wallet – and what the wealthy do to stay ahead. More importantly, you’ll learn how to start thinking differently about money in your own life. Let’s pull back the curtain on the financial game so you can stop playing blind.

Rule 1: Central Banks Create Money from Nothing – And It Benefits the Few

One of the most hidden-in-plain-sight truths is that money can be created out of thin air, and it’s done by those in power. Central banks like the U.S. Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, or the Central Bank of Kenya have the extraordinary ability to issue new money with a few keystrokes. This isn’t backed by gold or necessarily by any tangible asset – it’s fiat money, valid because the government says it is. When you hear about “printing money,” it often refers to central banks expanding the money supply through policies like lowering interest rates, buying bonds (quantitative easing), or outright lending to governments.

Why does this benefit the few? Because of something economists call the Cantillon Effect: the first recipients of new money enjoy it the most. When a central bank creates new money, it typically flows to major banks, government spending, or large corporations first. These actors get to use the money at current prices. By the time this money circulates to the average person, prices of goods and assets have often risen (since more money is now chasing the same goods). In other words, those at the top get newly created money before inflation kicks in, while everyone else feels the price increases later on.

Consider how governments finance deficits. Often, if tax revenues and borrowing aren’t enough, a government may indirectly have its central bank finance the shortfall – basically creating new currency units to cover the gap. This might avert immediate crisis, but it quietly devalues the existing money in circulation. It’s like slicing the same pie into more pieces; each piece (each currency unit) becomes a bit smaller. The public is rarely taught how this works. The system prefers you think of money as scarce and hard-earned – and for individuals it is – but at the top, it can literally be conjured when needed.

We saw a dramatic example of money creation in the early 2020s. In response to economic shutdowns, major central banks injected trillions of dollars into the global economy. While this stimulus prevented collapse, it also propped up financial markets. Stock prices and real estate values skyrocketed. Who owns most of these assets? Wealthy investors and institutions. Thus, those who held assets watched their wealth balloon, courtesy of newly created money. Meanwhile, regular people got stimulus checks or relief that was helpful but much smaller – and now they face higher costs of living (from food to housing) as a side effect of the same money printing. The average person paid for those policies via later inflation, even if they didn’t realize it.

In African markets, the dynamic is similar. Central banks in countries like Nigeria or Kenya also have printed money or expanded credit to cover government needs or stabilize banks. This often leads to currency depreciation and inflation. For instance, if the Central Bank of Nigeria finances government spending or bailouts by increasing the money supply, the value of the naira falls. Wealthy Nigerians often see it coming – they move assets into dollars or real estate. By the time the ordinary Nigerian realizes prices for basic goods have shot up, the well-connected have already protected themselves. Essentially, those who create or are closest to the creation of money benefit, while those farthest from it (ordinary citizens) see their savings diluted. It’s a hidden rule of modern finance: control the money supply and you control the game.

Rule 2: Inflation Is a Hidden Tax – and You Weren’t Meant to Notice

Inflation is often talked about as a mysterious force: prices just go up over time, right? But inflation is not an accident of nature – it’s largely a result of policy and monetary mechanics, and it acts as a hidden tax on the public. When more money is created (as in Rule 1) or when supply of goods lags behind demand, prices rise. The cost of living increases means each unit of currency buys less than before. If your income doesn’t rise at the same pace (and it usually doesn’t for most people), you effectively got poorer. That lost purchasing power is value that went somewhere – and indeed, it transfers to those who have assets or debt.

How is inflation a tax? Imagine you have saved $1,000 under your mattress. At a 10% annual inflation rate (extreme, but not unheard of in places like Nigeria recently), that cash would only buy what $900 could a year before. You “paid” $100 in lost value without any law ever being passed to take your money. Governments actually benefit from this erosion because if they owe large debts, those debts become easier to pay off in inflated currency that’s worth less. It’s like paying off an old loan with cheaper money. In effect, inflation silently taxes anyone holding cash or earning a fixed wage, and the beneficiaries are big borrowers (governments, large companies) and asset owners.

Elites understand this intuitively. They often position themselves on the winning side of inflation. Instead of keeping wealth in cash, they hold assets that rise in value when inflation hits. Real estate is a classic example: property prices tend to increase when construction costs and land prices go up with inflation. If a wealthy investor owns an apartment building, they can charge higher rent over time and the property value grows, while any mortgage they have is fixed at yesterday’s prices. Similarly, stocks are shares in companies – and companies can often raise their prices when inflation rises, which can translate into higher revenues and stock values over the long term.

Meanwhile, the middle class and poor find their salaries lagging behind rising prices. Their groceries, fuel, and school fees cost more, but their income doesn’t keep up. If they had any modest investments or savings, those might not earn enough interest to beat inflation. For example, banks in Kenya might offer around 5% interest on a savings account, but if inflation is 7% annually, savers are losing purchasing power every year despite seeing a nominal increase in their bank balance. It’s a stealthy wealth transfer from savers to borrowers.

A real-world illustration: in Nigeria, inflation reached levels in the high 20s percent range by 2023 – the highest in decades. Ordinary Nigerians saw the prices of food and necessities skyrocket. But consider someone who owned a lot of land or goods – the nominal value of their holdings went way up in naira terms. If a businessman had taken a big loan in 2018 to invest in, say, manufacturing equipment, by 2023 the real value of that loan had eroded dramatically due to inflation, effectively making it cheaper to pay back. The bank that lent the money gets paid back in naira that buy far less than when the loan was given. The winner? The debtor-investor, assuming they invested wisely. The losers? Anyone holding onto naira savings or earning the same paycheck as before, now stretched thinner.

It’s not that central banks and governments want runaway inflation – in fact, they try to manage it to a modest level. But they also quietly benefit from a bit of inflation, and certainly a surge can save them in desperate times (by reducing real burdens of debt). The “system” doesn’t highlight how you could personally counteract inflation, because consumption and simple saving are often encouraged instead. The hidden rule here is: inflation will always quietly erode the uninformed person’s wealth. To protect yourself, you must do what the insiders do – invest in things that rise with inflation, and don’t sit on cash. If you treat inflation as a given, you can actually harness it: owning assets, or even holding some hard currencies or commodities, can put you on the side that gains from the inflation tax instead of paying it.

Rule 3: Money Loves Speed – The System Keeps You Slow

Have you ever noticed how slow traditional finance is for regular people? You deposit a check and it takes days to clear. Apply for a loan and you drown in paperwork, waiting weeks or months for approval. Yet, behind the scenes, big money moves lightning-fast. This is by design: the system keeps the average person’s money moving slowly, while the wealthy and institutions trade and transact in microseconds. In the world of money, speed is power – and the insiders know it.

Banks and financial institutions use your money the moment it hits your account. If you deposit funds, the bank can turn around and lend most of it out or invest it immediately (thanks to fractional reserve banking). But if you want to withdraw a large sum or send money internationally, you might face delays or scrutiny. The structure is such that your money works for the bank first, and for you second. Each extra day they hold your funds, they have opportunities to profit – earning interest, charging fees, or investing – while you wait.

Meanwhile, those with capital and know-how arrange things so they never have to wait. Big investors often have lines of credit ready to deploy at a moment’s notice. Private equity firms can raise millions overnight when a hot opportunity appears. Elite traders use high-speed algorithms to arbitrage price differences in fractions of a second. If a major market event occurs (say a sudden stock drop or a currency devaluation rumor), the insiders are positioned to act before the news even becomes public. By the time average investors read about it in the morning paper or on social media, the best deals are gone.

This hidden rule is especially brutal during market crashes or rapid changes: when stock markets plunge or currencies wobble, the quickest players swoop in to buy assets at fire-sale prices. Slower actors – often regular folks – are still processing what happened or bogged down by process. For example, if a currency crisis causes the Kenyan shilling or Nigerian naira to drop sharply in value, well-connected players might quickly shift money into dollars or euros to protect themselves within hours. A middle-class worker, on the other hand, might not even realize what’s happening until they see the news at day’s end, by which time their savings’ value already fell. By the time they try to convert to a stable currency, the exchange rate has moved against them.

The system encourages you to be cautious and slow – think of the conventional advice to “wait for the right time” or submit to lengthy due diligence for even small financial moves – while the wealthy cultivate agility. They keep cash or credit on standby specifically to pounce on opportunities. They build networks to hear about deals before they’re public. A venture capitalist in Silicon Valley, for instance, often gets an early tip about a promising startup long before an IPO is announced to retail investors. By the time the average person is allowed in, the insiders have already bought low and are ready to sell high.

To break out of this dynamic, you should internalize the idea that money loves speed. This doesn’t mean being reckless; it means streamlining your finances so you can act decisively. It could be as simple as having an emergency fund or readily accessible investment account to deploy when markets dip. It means educating yourself to recognize opportunities quickly and not procrastinate until someone else (with faster reflexes or fewer hoops to jump through) seizes them. While banks might slow you down with red tape, find ways to minimize those frictions – use faster fintech solutions, maintain good credit to get quick loans if needed, and stay informed so you’re not the last to know important information. In a rigged game that keeps you waiting, sometimes your best move is to quietly step up your pace.

Rule 4: The Wealthy Don’t Keep Money – They Move It and Multiply It

One of the most counterintuitive lessons the rich understand is that money is not meant to sit idle. Average people are taught to save money in a bank, hold onto cash for security, and avoid taking “risks.” While prudent saving for emergencies is important, keeping large sums of money stagnant is actually risky in the long run – it steadily loses value (thanks to inflation, as we covered) and misses opportunities to grow. The wealthy have a very different approach: they almost never let money just sit; they are constantly moving it into investments that work for them.

Think about your paycheck. Perhaps you deposit it in the bank, pay bills, and whatever is left accumulates as cash savings. That savings might give you peace of mind, but after inflation and maybe taxes on the tiny interest, it’s hardly growing. Now consider how a wealthy individual treats their surplus money: they allocate it quickly into various asset classes. They might buy stocks, bonds, or real estate. They might fund a business or invest in a new venture. The point is, every dollar or shilling is viewed as a “soldier” that should be out there working and bringing back more value. Idle money is seen as lost opportunity.

This is a hidden rule because society’s conventional wisdom often glorifies the idea of a hefty savings account as the ultimate sign of financial prudence. It’s not that saving is bad – it’s that saving alone won’t make you wealthy. The system doesn’t advertise that because someone has to provide the capital for banks to lend out or for markets to use; if all your money stays parked in a low-interest account, it’s effectively being lent out to others who make higher returns. In Kenya and Nigeria, for instance, banks often pay modest interest on deposits but turn around and lend that money at much higher rates to businesses or government (through bonds) – the bank and the borrowers reap the rewards, while depositors barely keep up with inflation.

Wealthy people also understand the power of compounding and starting early. A dollar invested today can start earning returns immediately, which then can be reinvested to earn even more. Over years, this compounding effect is enormous. On the other hand, a dollar that sits idle for years not only doesn’t grow, it loses value. That’s why someone who begins investing or building assets in their 20s often ends up far richer by retirement than someone who saved cash under the mattress for decades and only started investing later. Time is a weapon in wealth building, and the rich use every minute of it.

It’s telling that for the wealthy, cash is a temporary asset – a parking place or liquidity pool to be used quickly. They might keep some cash for flexibility (as we discussed in the speed rule), but even that is strategic: it’s kept ready only to pounce on the next investment, not as the end goal. Real security to them isn’t having a pile of cash, it’s having multiple streams of income from investments. A rental property generating monthly rent, a dividend-paying stock portfolio, a stake in a profitable business – these are seen as true safety, because they outpace inflation and aren’t reliant on one employer or one account.

The average person can adopt this mindset in small ways. Instead of just saving for the sake of saving, save to invest. Set targets: once you have an emergency fund (say 3-6 months of expenses in cash for safety), direct additional savings into investment accounts or tangible assets. Make every saved shilling or naira ask, “What job can I do next?” Maybe it can buy a government bond, or a share of a solid company, or even be pooled with others to start a small business or buy a piece of land. The key is breaking the habit of letting money lounge around. The system won’t teach you this, because consumer banks profit from holding your deposits. But if you learn from the wealthy: money only matters when it moves – so put it to work for you as soon and as often as you can.

Rule 5: The Game of Interest – Pay It if You Must, Earn It if You Can

Debt and interest are often painted as villains in personal finance for ordinary people. You’re told to avoid credit card debt, be careful with loans, and pay down your mortgage as soon as possible. That’s good advice at the consumer level because high interest can indeed wreck a household budget. But here’s the irony: the entire financial system runs on the game of interest, and those who master the role of lender (the earner of interest) rather than just borrower (payer of interest) often accumulate great wealth. The wealthy understand that debt is a double-edged sword – dangerous if misused, but a powerful tool if used wisely.

Firstly, consider who earns interest: banks, bondholders, investors. Every time you pay interest on a loan or credit card, someone else is passively earning that money. Wealthy individuals and institutions position themselves to collect interest, not just pay it. They buy bonds (government or corporate) to earn steady interest income. They may provide private loans or invest in loan funds. Some even “be the bank” by financing deals and charging interest to borrowers. Meanwhile, the average person only encounters interest as a charge on their mortgage, student loan, or credit balance – always paying, never receiving.

Secondly, when the wealthy do borrow, they do it strategically. There’s a hidden rule in how debt can be used to one’s advantage: use other people’s money (OPM) to invest in appreciating assets. If you can borrow money at, say, 5% interest and invest it in something that yields 10% returns, you’ve made a profit on the spread. This is how real estate empires are built – using bank loans to buy property, renters pay the mortgage (and then some), and inflation eventually erodes the real value of the loan. By the end, the asset is owned outright and likely worth much more, while the loan’s burden was diminished by time and tenants. Businesses do this too, taking loans to expand operations that generate higher profits than the cost of the debt.

The system doesn’t encourage average people to think this way. We’re often simply taught “debt is bad” because for most uninformed consumers, consumer debt is bad – it’s used to buy depreciating items or fund lifestyles beyond one’s means. Credit card debt at 20% interest to buy new gadgets or expensive clothes is indeed a wealth killer. But not all debt is equal. Productive debt, used to acquire assets that produce income, is something the rich utilize frequently. They understand the nuance: avoid bad debt, leverage good debt. It’s a rule they play by, quietly amassing assets using borrowed funds, while publicly the narrative remains “debt is dangerous” to keep the masses from attempting the same moves.

Another aspect of this rule is minimizing paying interest whenever possible on personal consumption. The affluent often use tactics to avoid interest on things that don’t generate returns. They might pay cash or pay off credit balances each month. Or they might borrow through business entities at lower rates that also come with tax advantages (interest on business loans can be tax-deductible, for example). Many will lease cars or equipment through a business rather than take a personal loan – effectively letting them write off costs and not tie up capital. The point is, they are meticulous about not letting interest costs eat away at their wealth unless those interest costs are fueling a greater income.

For someone looking in from the outside, it can seem like the rich live in a different financial universe – one where they borrow freely yet never seem burdened. In truth, they are very calculated: they ensure they’re either on the collecting side of interest, or when on the paying side, it’s serving a plan to gain something bigger. To apply this rule in your own life, start by eliminating high-interest bad debts (credit cards, etc.) which only enrich your creditors. Then, consider how you might become an interest earner: buying bonds, peer-to-peer lending, even something like buying a rental property makes you the one receiving payments. And if you do borrow for investment (like a business or property), do it with a clear-eyed calculation that the returns should outweigh the interest. The system wants you to think all debt is scary so that you shy away from using financial leverage effectively – while banks happily collect interest from you. Flip the script where you can.

Rule 6: Influence Is Investment – Elites Shape the Rules in Their Favor

Money doesn’t operate in a vacuum; it’s deeply tied to politics, laws, and regulations. A largely unspoken rule of the game is that wealthy individuals and institutions invest in influence to ensure the playing field stays tipped in their favor. In other words, the rich often “buy” the rules of the game. This can range from lobbying for favorable legislation, funding political campaigns, to securing elite connections that grant insider knowledge or preferential treatment. Meanwhile, the average person is told that the system is fair and equal for all, and to simply vote and hope for the best. The truth is, those with money routinely use it as leverage to get more, by nudging the system itself.

Consider tax laws. Why do many billion-dollar companies or ultra-rich individuals pay a lower effective tax rate (as a percentage of income) than their middle-class employees? It’s not because of outright illegal evasion, but because the tax code is full of provisions that favor certain activities and forms of income that the wealthy are positioned to exploit. Capital gains (profits from investments) are often taxed at lower rates than wages. There are loopholes and deductions for things like real estate depreciation, business expenses, or offshore income. These didn’t appear by accident; they were lobbied into existence. Financial elites have teams of lawyers and lobbyists who work to create and preserve these advantages. In countries worldwide, including Kenya and Nigeria, large corporations and influential families negotiate special tax breaks or exemptions – sometimes justified as “incentives” for investment – that small businesses or ordinary citizens could never dream of getting.

Regulations too often end up favoring big players. A complex web of rules can actually raise barriers to entry in various industries, making it hard for newcomers (who often have less capital or connections) to compete. For example, if new banking regulations require expensive compliance systems, big banks can handle that cost, but a small upstart bank struggles. Thus, the regulation, perhaps touted as consumer protection or stability, incidentally helps keep big banks dominant. In Nigeria, for instance, the banking sector consolidation in the mid-2000s (where banks had to have a minimum level of capital) meant only larger banks survived or could merge, squeezing out smaller ones – which ultimately reduced competition. The public rationale was to have stronger banks (not entirely false), but it also conveniently concentrated market share.

Wealthy interests also shape monetary policy and economic policy to suit them. Central banks are often politically independent on paper, but they operate in an environment influenced by the concerns of the powerful. A government might pressure a central bank to lower interest rates before an election to stimulate a feeling of prosperity – a short-term boost that can inflate asset bubbles, benefiting those who own assets. Or consider how, during financial crises, policymakers design bailouts: large financial institutions (and their shareholders or bondholders) are saved from collapse by government intervention, because they are “too big to fail.” The average homeowner facing foreclosure or a small business going under typically doesn’t get the same lifeline. This was evident in the 2008 global financial crisis and in various national crises since – banks in the US and Europe got rescued, while ordinary people often lost homes and jobs. In Kenya, when certain banks have faced troubles, the political connections of those involved often dictated whether they were rescued or allowed to fail.

Another angle of influence: information asymmetry. The elite often have better and faster access to information. They might not be committing insider trading crimes, but they operate in spheres where they hear about changes and opportunities first. They attend World Economic Forum meetings, they sit on advisory boards, they have ministers on speed dial. When you know earlier that a policy change is coming – say a devaluation of currency, a change in interest rates, a new regulation – you can adjust your financial positions beforehand. This is perfectly legal if you just “happened to be in the loop,” but it’s not something the public enjoys. A rumor in the right circles that a subsidy will be cut or a tax added can lead a connected businessman to reposition assets, while the public is shocked when it becomes headline news days later.

The system doesn’t advertise this rule because it undermines the narrative of meritocracy and fair play. But the wealthy effectively treat influence as an asset class. They allocate funds to it like they would to stocks or real estate – because it pays dividends in the form of favorable conditions. For instance, a corporation might spend millions lobbying for a law change, which then saves them billions in the next decade. That’s a phenomenal return on investment. On a smaller scale, a local tycoon might generously fund and befriend political leaders, ensuring his businesses get government contracts or face less regulatory harassment – another “investment” paying off.

For the average person, it’s not feasible to buy political influence in the same way. However, understanding this dynamic can inform how you navigate your own life. Support policies that increase transparency and accountability, because opaque systems usually favor those with influence. Be aware that when something doesn’t make sense (“Why would the government do X if it hurts consumers?”), the answer often lies in who benefits behind the scenes. At a personal level, you can practice a form of this rule by expanding your own network and influence in your community or industry. Building relationships with mentors, advisors, or even local officials in an ethical way can give you an edge or early info that others might not have. While you can’t rewrite laws yourself, you can at least avoid being naive: realize that big players are tilting the field, and plan accordingly. That might mean diversifying your investments, not relying solely on one job or one country’s economy, and staying politically aware so you’re not caught off guard by changes that could affect your finances.

Rule 7: The Elite Hedge Their Bets – Geographic and Asset Diversification

If there’s one thing the wealthy absolutely do not do, it’s put all their eggs in one basket. A key hidden rule is that diversification isn’t just a buzzword, it’s a lifeline – and not just diversification in the stock portfolio sense, but across currencies, countries, and asset types. The global elite quietly spread their wealth and risks around so that no single government policy, economic downturn, or currency crash can wipe them out. On the other hand, most average people’s fortunes are entirely tied to one country and one currency (usually their salary in local currency and perhaps a home). The system doesn’t emphasize this kind of broad diversification to the masses; if anything, loyalty and keeping your money “at home” is encouraged. But the rich do the opposite behind closed doors.

Consider currency risk. If you live in Kenya, you likely earn and save in Kenyan shillings; if in Nigeria, in naira. When those currencies lose value against the US dollar or euro (which they have a tendency to do over long periods), your international purchasing power falls. Imported goods become more expensive, travel costs soar, overseas education for your kids costs more local currency, and so on. Wealthy individuals in these countries are painfully aware of this risk – because many have seen fortunes evaporate during periods of rapid devaluation or hyperinflation (African histories are replete with such episodes, from Zimbabwe’s hyperinflation to periodic naira and shilling slides). Thus, they hedge by holding hard currencies or assets denominated in them. Elite families might keep a significant portion of their wealth in U.S. dollars, euros, or even stable cryptocurrencies and gold. They maintain foreign bank accounts or offshore companies in financial hubs. So when the local currency drops, their core wealth is preserved or even gains in local terms.

Geographic diversification is another layer. The rich often own real estate in multiple countries – perhaps a flat in London, a condo in Dubai, a vineyard in France, etc. They might run international businesses or hold foreign stocks. This means if their home country faces political upheaval, economic crisis, or new punitive taxes, they can shift focus or assets elsewhere. In many developing countries, the ultra-wealthy have contingency plans: second passports or residency permits abroad, homes overseas, and foreign education for their children, essentially insuring themselves against local instability. For instance, many Nigerian billionaires have substantial assets in the UK or US. Many Kenyan business magnates have ties to Dubai or Europe. This isn’t lack of patriotism – it’s a calculated financial strategy. They know that no single market is guaranteed, so they always have a foot in another.

Even within a country, elites diversify asset types. They own businesses across different sectors – if one industry slumps, another might boom. They purchase government bonds, which do well when stock markets falter (and vice versa). They might hold commodities like oil futures, or art and collectibles that don’t correlate with stock market movements. You often hear phrases like “alternative investments” – fine art, rare wine, stakes in private companies, etc. These are things average folks rarely consider, but the wealthy do, because they seek uncorrelated assets that won’t all crash at once. If the stock market tanks, maybe their art collection still holds value or their gold investment shines. If a real estate bubble bursts, maybe their tech startup shares are skyrocketing.

Importantly, the system doesn’t openly teach the average person to diversify internationally or into exotic assets – in fact, many countries have had strict rules limiting citizens from moving money abroad or investing offshore. It can be quite difficult for a middle-class person to, say, open a bank account in another country or buy foreign stocks, due to regulatory hurdles or simply lack of knowledge. Those restrictions and complexities act as friction to keep local capital in place (which helps the local economy and banks). However, those with enough wealth can always find advisors to navigate around controls – setting up holding companies, using dual citizenship, or lobbying for exceptions. The result: capital mobility for the rich, capital immobility for the rest.

So, what can you take from this hidden rule? Think globally about your money. Even if you’re not rich, you can start diversifying in small ways. For example, you might hold a portion of your savings in a stable foreign currency if your country allows it, or invest in international mutual funds or ETFs that give you exposure to other markets. Perhaps consider owning some gold or other commodity as a hedge against currency weakness. If you are entrepreneurial, consider markets beyond your own country for your product or services, so a local downturn won’t sink you. This isn’t to encourage capital flight or neglecting your home country – it’s about personal financial resilience. The elites sleep easier because they know a crisis in one place won’t destroy them; it’s worth aiming for a sliver of that peace of mind by not betting everything on one economy or one form of asset. Diversification is the closest thing to a free lunch in finance, and the fact that the wealthy are so keen on it while it’s not drilled into the rest of us is telling.

Rule 8: Financial Education Is Reserved – You’re Meant to Stay in the Dark

Perhaps the most fundamental hidden rule underpinning all others is the unequal distribution of financial knowledge. If the rules we’ve discussed so far sound unfamiliar or eye-opening, it’s because most people simply aren’t taught how money really works. Think about your formal education: schools and universities teach us how to be good workers in our fields, but rarely teach how to manage money, how banking works, how to invest, or how governments affect the economy. This omission is not an accident or conspiracy so much as a structural quirk: an uneducated populace about money is easier to keep playing by the traditional script (earn → pay taxes → save a bit → spend the rest). The system benefits from financial illiteracy. The less you know, the more you’ll rely on the “experts” and the status quo – and the status quo largely favors those already in power.

Elite families ensure their children learn these concepts early, if not at home then through costly education or mentorship. Meanwhile, public education glosses over personal finance. When’s the last time a high school class taught about inflation’s effect on savings, or how compound interest can work for or against you, or how central bank policies might impact your job prospects? These are seen as specialized topics, yet they critically shape everyone’s life. By keeping such subjects out of general curricula, society ends up with citizens who might master professional skills but flounder in financial matters. They might fall prey to high-interest debt, fail to invest for the future, or panic during market cycles – all of which ultimately benefits financial institutions that collect interest, fees, or cheap assets in fire sales.

There’s also a media dimension to this. Financial news can be bewildering and often geared toward either other experts or pushing a narrative that supports market sentiment. The average person, busy with their job and family, hears snippets: stock market up, Fed did this, inflation number that – without a clear, accessible explanation of what it means for them. It’s easy to throw up one’s hands and assume “someone else is handling it” or that it’s too complex. Unfortunately, that’s exactly what maintains the divide. The less people understand, the more they might, for instance, panic-sell investments at the wrong time, or vote for a policy that sounds good but hurts them economically, or trust a get-rich-quick scheme because it’s the only advice on money they’ve ever received (from a YouTube ad rather than an academic curriculum).

Additionally, misinformation and distractions play a role. Society bombards us with consumerist messaging (which we’ll discuss in the next section), but also with fatalistic narratives like “you need to be lucky or ruthless to be rich” or “money is the root of all evil.” Such ideas can subconsciously lead people to shy away from proactively learning about finance or aiming higher in wealth accumulation. If deep down you feel money is dirty or that the system will just crush your efforts, you might not even try to change your situation. Meanwhile, the wealthy obviously do not subscribe to those limiting beliefs – they understand that money is a tool, not a moral indication of one’s worthiness, and that the system can be navigated and even beaten with knowledge and strategy.

The encouraging news is that financial knowledge is more accessible now than ever, for those who seek it. The internet is a double-edged sword: while full of noise and bad advice, it also offers high-quality resources (often free) – from courses on investing to forums where people share experiences about budgeting, to articles dissecting economic policies. People in Kenya, Nigeria, and everywhere else can now learn what Wall Street traders or London bankers know, if they dedicate the time. We see more youths in African countries getting interested in stocks, cryptocurrency, forex trading, etc. – not all will succeed, and some plunge in without enough prep and get burned, but it’s a sign of an awakening desire to crack the money code.

Yet, even here, caution is warranted: the system doesn’t necessarily want a financially savvy population, so not all information out there is equal. Predatory advisors and scams often target those hungry for financial success but lacking foundational knowledge. The key is to start with basics (the very concepts covered in this blog: inflation, compound interest, diversification, etc.) and build up a solid understanding before chasing complex strategies.

Recognize that educating yourself is an act of empowerment that the status quo might not have encouraged, but cannot stop. The hidden rule is that knowledge is guarded – but you now have the chance to breach that guard. By doing so, you essentially acquire a new lens to view every other rule: you’ll see through marketing that urges you to spend, you’ll grasp what politicians really mean in economic promises, and you’ll be able to plan your finances in a way that aligns more with how successful people do. In short, the more you learn, the less you’ll fall for the traps the system sets. Make no mistake, self-education in finance is a revolutionary act in a world that banks on your ignorance.

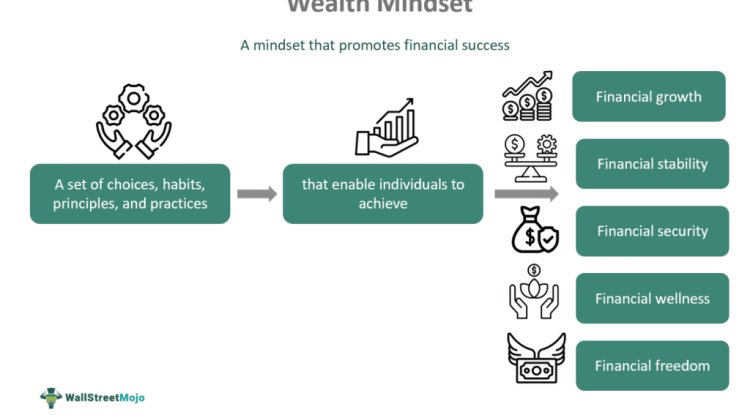

Rule 9: Owning Beats Earning – The Focus on Assets, Not Just Income

A crucial distinction separates how the wealthy view money versus how everyone else does: most people focus on earning income, while the rich focus on building assets and equity. In other words, having a high salary is nice, but owning things that generate income (even when you’re not working) is ultimately far more powerful. The system quietly perpetuates the idea that a bigger paycheck is the path to wealth – encouraging you to climb the career ladder, negotiate raises, perhaps get advanced degrees to earn more. While there’s nothing wrong with better income, the hidden rule the rich follow is that wealth comes from ownership, not just labor.

Why is equity so important? Because equity (ownership) in an asset can grow exponentially and can keep paying you indefinitely. If you own shares in a company (even your own small business), those shares can increase in value many times over if the company succeeds, and they might pay dividends along the way. If you own a rental property, your tenants effectively earn money for you month after month, and the property itself may appreciate. If you own intellectual property (like a book, a patent, a piece of software), you can earn royalties or licensing fees while you sleep. Contrast this with a salary: you trade your time for money, and if you stop working, the income stops. Even a high salary usually just leads people to spend more (a phenomenon known as lifestyle inflation – you make more, you upgrade your lifestyle, and the extra income vanishes). Moreover, salaries are typically taxed at a higher rate than many forms of investment income. Many wealthy individuals intentionally keep their “income” (salary) low to minimize tax, while most of their financial growth comes from capital gains, business profits, and other asset-based flows that often enjoy tax advantages.

The system encourages income chasing in subtle ways. Society praises job promotions and titles, not the stealthy accumulation of rental properties or dividend stocks. Governments even publish data and talk about “average incomes” as a measure of prosperity, but rarely highlight “median net worth” or asset ownership distribution, because that would starkly show the disparity. In places like Kenya and Nigeria, a lot of public discourse is about employment – creating jobs, getting degrees to secure a good job, etc. Those are important, but little attention is given to helping ordinary people become capital owners. For instance, how many people in these countries have access to stock markets or own part of the businesses they work for? Very few, relative to the population. Stocks or government asset privatizations often end up largely in the hands of those who already have capital or connections.

Elite strategy often involves turning income into assets as quickly as possible. An entrepreneur might take a modest salary from their own company but plow profits back into expansion (building the company’s value – their asset). A corporate executive might use bonuses to purchase real estate. Even young professionals in wealthy circles are taught: use your earned income to acquire something that will keep earning when you’re not working. In contrast, someone might get a raise and immediately think about buying a better car or a luxury consumption item – which doesn’t generate future income, it actually creates new expenses (maintenance, insurance, etc.). Owning a flashy car might boost status, but it’s not boosting net worth; the wealthy know the difference, and often delay gratification or curb visible consumption in favor of acquiring assets first. It’s why you sometimes hear stories of millionaires who live in modest homes or drive an older car – their priorities are different from what the marketing-driven consumer culture pushes.

Now, shifting to an ownership mindset doesn’t mean everyone should start a company or that it’s easy to just go buy assets with limited funds. But small steps count. Buying even a few shares of a solid company means you are now a part-owner of a productive asset. If your employer has a stock purchase plan or a retirement fund, take advantage of it – that’s ownership in the works. Instead of only thinking “how can I earn more,” start thinking “how can I own more.” Own more skills (that’s an intangible asset that can earn you income in various ways), own part of your home instead of renting (if feasible), own equipment that could be rented out or used for a side business. The key is, once you acquire something of value, it can work for you beyond your own hours.

The system doesn’t want a mass shift toward ownership for the general population, because the current paradigm relies on most people being workers and consumers, not owners. If too many people become financially independent owners, who will staff the offices and factories or reliably pay interest on loans? But in truth, broad ownership is the real foundation of a stable and prosperous middle class (some economies encourage it through policy, e.g., Singapore’s push for citizens to own homes or the U.S.’s historical promotion of stock investing for retirement). In places where this is lacking, you see more stark divide: a tiny owner class and a huge working class. Recognizing this hidden rule – that equity matters more than income – can inspire you to gradually pivot. Even if you love your job and career, think about what you’re building on the side for yourself. The wealthy person’s salary is just a means to acquire wealth, whereas for most others it’s the end in itself. Change that perspective, and you’ll start finding ways to turn money into lasting wealth.

Rule 10: Your Consumer Habits Make Them Rich – So They Encourage Spending

We end with a reality that hits close to home for everyone: every dollar or shilling you spend is someone else’s income. That by itself isn’t nefarious – that’s just commerce. But the hidden rule here is that the system relentlessly encourages you to consume, because your consumption is the source of wealth for those who own the businesses you buy from. The rich have a saying: “Either you work for money, or money works for you.” When you’re the consumer, you’re effectively working for the moneyed interests by handing over your earnings in exchange for goods and services. The elite, understanding this, position themselves on the side of production and investment. They want to own the store, not just shop in it.

Modern society is arguably built on consumerism. We are bombarded with ads, influencers, and societal pressures to spend: the latest smartphone upgrade, fashionable clothes, streaming subscriptions, eating out, you name it. Entire industries thrive by creating needs out of wants and nudging you to part with your cash routinely. For the average person, it’s easy to get trapped in a cycle of earn → spend → earn more → spend more. This leaves little capital left to invest or save; meanwhile, those who own shares in the companies you patronize see their profits and stock values grow. Every time you buy a product from, say, a multinational company, you’re enriching its shareholders – many of whom are likely wealthy individuals or investment funds. And if you happen to carry a balance on a credit card to finance that consumption, you’re also enriching banks via interest (tying back to Rule 5).

The system’s narrative is that buying more is a sign of success – think of all the slogans like “treat yourself” or the expectation that as soon as you get a raise you “deserve” a nicer car or bigger house. If people en masse started living frugally and investing their surplus, there would be short-term economic hiccups (consumer spending drives a lot of economies, after all). But more importantly, it would shift power: widespread frugality and investment would mean more people accumulating capital, and fewer easy profits for companies reliant on frivolous or status-driven purchases. So there’s a subtle but constant push: celebrate consumption. Holidays and sales events every other month, new versions of products rolled out deliberately to stoke FOMO (fear of missing out), and even social media making spending visible and therefore competitive (“Keeping up with the Joneses” is now on a global, digital scale).

Wealthy individuals often play both sides psychologically. They might enjoy luxury, but they usually spend a smaller fraction of their income on consumption than the middle class does. To use an example: if a billionaire buys a $200,000 car, it’s perhaps 0.1% of their net worth. If a middle-class professional buys a $40,000 car on loan, that might be 100% of their annual income, perhaps 50% of their net worth – a far bigger impact. The rich person’s life won’t change if they lose that $200k; the average person might be financially stressed for years to make payments on that $40k car. The wealthy know this, so they let the businesses they own cater to people’s desires for status and convenience, skimming profit off it. Some of the most profitable companies are those selling relatively low-cost items in massive volume – fast food, snacks, cheap fashion – essentially drawing small amounts from millions of people’s pockets daily. It adds up to huge wealth… for the owners.

In places like Kenya and Nigeria, consumerism has also taken root as economies grow. There’s rising demand for smartphones, designer clothes, entertainment subscriptions, imported cars, etc. The aspirational lifestyle marketing is everywhere. However, consider who often owns the companies supplying these: multinational corporations or a few powerful local conglomerates. The money spent on, say, a luxury imported champagne in Lagos ultimately goes to the French producer and its shareholders abroad; the money spent on an iPhone in Nairobi boosts Apple’s profits and its mostly Western shareholders. Even local companies, if publicly traded, see their stock value rise if they can tap into a growing consumer base. Who owns a lot of stock in African firms? Often foreign investors or domestic wealthy elites. So again, the everyday spending of the working and middle class transfers wealth upwards.

The hidden rule isn’t “don’t buy things” – we all need and want things, and enjoying your life is important. Rather, it’s be mindful that your spending is someone else’s passive income. Aim to flip that script in at least some areas of life: can you own shares of the companies you frequently buy from, so you get some money back in dividends or appreciation? Can you start a side business to capture some consumer spending in your community? Even choosing to support local small businesses keeps money circulating among the community rather than all flowing to big corporates. The wealthy often invest in or start businesses precisely to be on the receiving end of consumer behavior.

At the personal finance level, adopting some frugality and intentional spending frees up resources for you to invest in yourself and assets. It might not be glamorous in the short term – skipping the latest gadget upgrade or brewing your coffee at home doesn’t give an immediate thrill – but if you channel those savings into stocks, a mutual fund, or seed money for a future property or enterprise, you are effectively redirecting the wealth flow. Over time, the returns from those investments could pay for many gadgets or coffees without denting your principal. That’s how the rich think: delay some gratification, buy assets that pay you, and let those pay for the gratification later.

The system of constant consumption is a cornerstone of why the rich get richer; they’ve set it up so that it’s almost automatic. Knowing this, you don’t have to be a sucker for every sales pitch. You can become a bit more immune to the “buy, buy, buy” mantra and design your own mantra of “invest, own, and enjoy sustainably.” Every coin you keep and invest is a coin that can generate more for you, rather than immediately enriching someone who’s already wealthy. It’s a small act of rebellion against a cycle that was never meant to make you rich – only to make you spend.

Conclusion

The world of money is governed by rules that are often unstated but very much in play. We’ve pulled back the curtain on several of these hidden money rules – from the mechanics of central banking and inflation to the savvy maneuvers of the wealthy in leveraging speed, debt, influence, diversification, education, ownership, and consumer behavior. You might feel a mix of enlightenment and unease: enlightened because now you see patterns that were always there, and unease because it’s clear the game has been tilted from the start. That’s normal. Remember, the goal of revealing these truths isn’t to incite despair or cynicism, but to empower you to think and act differently going forward.

No matter your current financial situation – whether you’re in Kenya, Nigeria, or anywhere else – knowledge is the first weapon to change your trajectory. Global or local, the principles hold: inflation will eat your lunch if you let it, so don’t leave your wealth in cash alone. The powerful will use their power, so be aware and adjust your strategies (even if you can’t change them, you can avoid being blindly on the losing side). Opportunities favor the prepared and swift, so get your financial house in order and stay alert. Assets beat income in the long run, so whenever possible, acquire things that put money in your pocket. And perhaps most importantly, continuous learning will keep you ahead of the curve – make it a habit to educate yourself on finance, economics, and investing, because the rules can evolve and new opportunities (or threats) will arise.

It’s also worth noting that while the system may not want everyone to know these rules, nothing is stopping you from using them ethically to your advantage. There’s no law against thinking like a wealthy person. You don’t need to be ruthless or unethical; you can play smarter within the rules once you know them. Build a side hustle or business with an eye on providing real value (and thus create an asset for yourself). Connect with communities of like-minded individuals who share financial knowledge (there are many online forums and local groups springing up, including in African cities, where people exchange tips on investments, real estate, and personal finance). Advocate for better financial literacy in your circles – after all, the more people around you who understand these concepts, the more robust your community’s economic health will be.

Lastly, understand that change takes time. The wealthy families we observe often have a generational head start. If you’re starting fresh to implement these insights, don’t be discouraged by initial slow progress. The system counted on people giving up or not trying. Even small moves – starting an emergency fund, buying a few stocks, paying off a toxic debt, reading a finance book – put you on a different path than before. And those small moves compound, much like money does. Over years, they can lead to significant improvements in your financial security and freedom.

The system may not want you to know these rules, but now you do. The knowledge is in your hands. What you do with it could transform not just your bank account, but your entire perspective on life and freedom. Money is not an end in itself, but understanding money is a means to take control of your destiny. Use these hidden rules for good: to improve your family’s future, to support your community, and to break free from any financial chains that have limited you. The playing field might not become fair overnight, but you’ve just equipped yourself to navigate it far more effectively. In the grand game of wealth, may you now play it with eyes wide open – and perhaps even change the game for the better as you succeed.

What's Your Reaction?