7 Money Rules the System Doesn’t Want You to Know – Build Wealth in Kenya and Beyond

Discover the 7 hidden money rules the rich use to build lasting wealth. Learn how to invest, leverage good debt, outsmart banks, live below your means, and create multiple income streams in Kenya and beyond.

Most people play by the financial rules society taught them – go to school, get a job, save money in the bank, avoid debt, and maybe retire someday. Yet, why do so many hard-working people still struggle financially? It turns out there are money rules the “system” would prefer you never learn. By "the system," we mean the traditional financial establishment – banks, schools, and those who profit when the average person stays financially naive. These institutions benefit when you follow conventional advice blindly, because your ignorance is their profit. As one financial educator famously put it, “The stupider you are with your money, the richer your banker gets.” In this comprehensive guide, we’ll reveal 7 powerful money rules that aren’t taught in school – rules the system doesn’t want you to know – and show you how to use them to build wealth.

We’ll dive into why working more hours won’t make you rich, why saving alone is not enough, how debt can be a tool for wealth, and other eye-openers. Each rule is explained in depth, including how it differs from mainstream advice and how the system profits from keeping people in the dark. We’ll also give actionable steps for you to apply these rules, with real examples from Kenya and Africa – from SACCO dividends to M-Pesa mobile money, from land investments to stock market tips. By the end, you’ll be armed with knowledge to take charge of your financial future. Let’s get started with the rules the rich and the system would rather you not figure out.

Rule #1: Stop Trading Time for Money (Your Salary Alone Won’t Make You Wealthy)

What this rule means: If your only plan to become wealthy is to work more hours or climb the job ladder for a bigger salary, you’re playing a losing game. Trading your time directly for money – as most employees do – puts a hard cap on your income. There are only 24 hours in a day, and you need to sleep and have a life too! Wealthy people understand that no one becomes truly rich solely from a paycheck, no matter how high. They focus on earning money in ways not directly tied to time, such as owning businesses, assets, or investments that generate income even when they aren’t personally working.

Mainstream vs. reality: Society praises hard work and steady jobs, and indeed having a job is important – but working harder or longer at a job has diminishing returns. Mainstream advice might say “work overtime, get a promotion, save more from your raise.” Yet many people with good jobs still live paycheck to paycheck. The reality is that a salaried job, even a high-paying one, usually won’t create significant wealth because your labor doesn’t scale. An hour of work gives you one hour’s pay, whereas an asset (like an investment or business) can earn for you 24/7. As entrepreneur Keith Cameron Smith bluntly said, “Trading time for dollars is a loser’s game, especially as technology destroys many jobs that don't require a highly skilled human being.” In other words, relying only on your labor income is risky in the long run – you could work tirelessly, yet automation or layoffs could erase your livelihood.

Why the system wants you unaware: The system needs you to trade time for money. Schools groom us to be employees – to get a good job, not to become investors or entrepreneurs. Companies and governments rely on a large workforce of people who exchange their time for wages (and pay income taxes on those wages). If everyone aimed to be an owner instead of an employee, who would staff the offices and factories? By keeping people content with a salary, the system ensures we remain workers (who generate profits for business owners and pay taxes) rather than becoming independent wealth-builders. The system is comfortable when you think “overtime will solve my financial issues” instead of learning how to make money work for you.

In Kenya and Africa, this dynamic is evident. Many educated professionals with stable jobs still struggle financially, while traders, entrepreneurs, and investors often leap ahead. For example, you might earn a decent salary in Nairobi, but if you spend it all on living expenses, you won’t get ahead. Meanwhile, a business owner in Kariobangi or a farmer in Eldoret could be growing assets (inventory, land, crops) that eventually far exceed a salary earner’s net worth. Working harder at your job is honorable, but it won’t automatically make you rich – you need to break the direct link between hours and shillings.

Action Steps – How to Apply Rule #1:

-

Build Income Streams: Start developing income sources besides your salary. This could be a side hustle or small business, rental income from property, or freelance gigs using your skills. Even a part-time venture can grow into a significant asset over time. The goal is to have money coming in from multiple channels, so you’re not reliant on a single paycheck.

-

Focus on Scalable Work: If you have entrepreneurial ambitions, choose businesses that can grow without requiring you to do all the work. For instance, an online store can keep selling products overnight, or a boda boda (motorbike) owner can earn by hiring riders. Contrast this with something like consultancy or manual labor, where your presence = income. Look for leverage.

-

Invest in Assets that Work for You: We’ll cover investing more in Rule #2, but keep in mind that investments are a way to earn without active labor. Owning shares in a company means your money is earning from that company’s employees’ work. Owning rental units means earning from tenants’ rent while you sleep. Shift from only earning by your sweat to earning from assets you control.

-

Use Your Job to Fuel Your Freedom: While you do rely on a salary, use it wisely. Live on less than you make (more on that in Rule #6) and channel surplus income into building assets. Your job can be the initial engine that funds your investments or business ideas. For example, if you’re a teacher or office worker, you might save to buy a matatu (minibus) that generates daily fares, effectively turning salary into an asset.

-

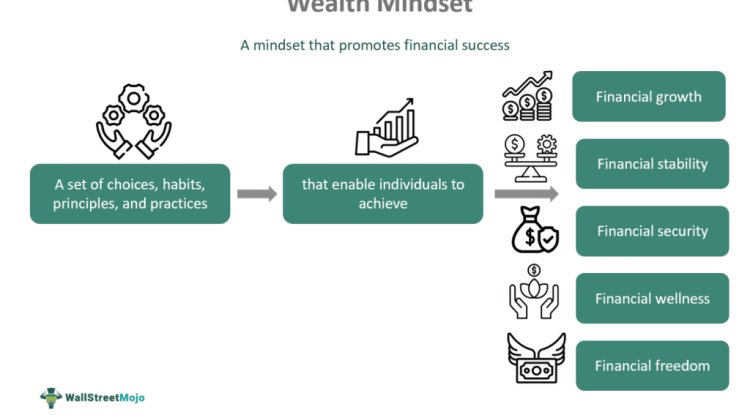

Mindset Shift – Think Like an Owner: Begin viewing your time as valuable and limited. Ask, “How can I make money without me doing all the work?” This might involve hiring others, using technology, or pooling resources with partners. Even within your job, seek opportunities for equity or profit-sharing if possible (some companies offer stock options or bonuses based on company performance – which aligns you more with ownership). The key is to transition from a pure worker mindset to an owner mindset.

By recognizing that your time is your most limited resource, you’ll prioritize ways to uncouple your earnings from hours worked. This is the first step to breaking out of the middle-class trap of endless work with little to show for it.

Rule #2: Don’t Just Save – Invest (Saving Alone Is Not Enough to Grow Wealth)

What this rule means: Simply saving money will not make you rich – you must invest it so that it grows. Saving is often touted as the cornerstone of personal finance (and yes, having savings is important for emergencies), but keeping all your money in a savings account or under the mattress actually makes you poorer over time once you factor in inflation. Investing means putting money into assets that generate returns – such as stocks, bonds, real estate, a business, or even a high-yield SACCO – so that your money is working for you and multiplying. The wealthy prioritize investment returns, while the average person often mistakenly thinks just piling up cash is enough.

Mainstream vs. reality: The mainstream financial advice for decades has been “save, save, save.” We’re told to budget and put a portion of our salary in a savings account. That’s fine for short-term goals or an emergency fund, but saving alone won’t build wealth because cash sitting idle doesn’t grow; it shrinks in real value. Consider Kenya’s case: consumer price inflation in Kenya has averaged about 6.3% annually over the last decade. Meanwhile, a typical bank savings account might pay you only around 3-4% interest per year (often even less). In mid-2025, the average savings account rate in Kenyan banks was about 3.3-3.8%. Some accounts pay as low as 0.5% per annum interest, and very few might go up to 7–8%. Do the math: if inflation is ~6% and your savings earn 3%, your money’s purchasing power declines by about 3% a year. You’re effectively losing money by just saving! This is why many who diligently save for years feel frustrated – the price of land, food, or school fees rises faster than their bank balance. Reality: To get ahead, your money must earn more than inflation – which usually means investing it in higher-return assets, not just a standard savings account.

Why the system wants you unaware: The system – especially banks and governments – actually benefits when you just save cash traditionally. How so? Banks take the money you deposit and lend it out at much higher interest rates. For example, Kenyan banks in 2025 were charging around 15% interest on loans while giving savers ~3-8%. That spread (the difference) is the bank’s profit, which is essentially your money making money for the bank, not for you. They love customers who keep large savings balances at low interest, because it’s cheap capital for them to on-lend. Additionally, when you don’t invest and just hold cash, inflation (which governments and central banks control via money printing and policy) quietly eats your savings – effectively a hidden tax that benefits large borrowers and the government (their debts become cheaper in real terms while your savings lose value). In short, the system prefers you to be a passive saver rather than an active investor. Schools rarely teach about investing for this reason – an informed investing public would demand better rates or move money into investments, which makes it harder for banks to exploit the spread and harder for governments to run up debts without hurting voters. Instead, we hear benign advice like “open a savings account for your future,” which by itself is incomplete advice.

Kenyan/African context: Many Kenyans can relate to saving diligently via M-PESA or bank accounts, only to find that after a few years, the amount buys much less. For instance, if you stashed KSh 100,000 in a bank account at 3% interest, you’d have ~KSh 115,000 after five years. But if inflation averages 6%, you’d need ~KSh 133,000 to maintain the same buying power – meaning your 115K is a loss in real terms. On the other hand, those who put money in a Chama or SACCO that invests in, say, land or pays higher dividends often see better growth. Some Kenyan investment groups buy plots of land and resell after value appreciation – far outpacing inflation. Even simple moves like buying Treasury bonds (which often yield ~10-12% in Kenya) or investing in mutual funds/money market funds (which might yield 8-10%) would beat a savings account. The difference is huge over time.

The rich understand that cash is trash if left idle – they seek assets. If you look at an average wealthy individual’s portfolio, only a small portion is in cash savings; the rest is in investments (stocks, real estate, businesses, etc.). They let compound interest and asset appreciation do the heavy lifting.

Action Steps – How to Apply Rule #2:

-

Start Investing Early and Regularly: You don’t need a fortune to begin investing – start with whatever you have, and do it consistently. If you’re in Kenya or Africa, consider accessible investment avenues: for example, unit trusts or money market funds (some allow starting with as little as KSh 500 or KSh 1,000) which often yield better than savings accounts. The earlier you start, the more you harness the power of compounding (earning interest on interest).

-

Beat Inflation: Aim for investments that historically outpace inflation. In Kenya, this could include Treasury bonds (government bonds) which often pay interest around or above inflation (e.g., a 5-year bond might pay 11% interest, comfortably beating 6% inflation). Real estate or land is another favorite – land values in growth areas often rise faster than inflation (though do your homework on location and price). Stocks can also beat inflation over the long run; for instance, investing in strong companies on the Nairobi Securities Exchange (NSE) like Safaricom or Equity Bank could provide dividend income and capital growth that outpaces inflation in the long term.

-

Use SACCOs and Chamas Wisely: As an alternative to low-interest bank accounts, Savings & Credit Cooperatives (SACCOs) in Kenya offer attractive returns. Many SACCOs pay annual dividends on shares and interest on deposits far higher than banks. For example, top Kenyan SACCOs in 2025 paid dividends of 15–20% and interest on member deposits often above 10% – that’s money back into your pocket as a member-owner. If you join a reputable SACCO, your savings there effectively become an investment that can yield inflation-beating returns (plus you get access to low-interest loans). Similarly, a well-run Chama (investment group) can pool funds to invest in high-return projects (like real estate or a business). Action: Research SACCOs in your field or community, and consider allocating some savings there for better growth.

-

Diversify Your Investments: Don’t put all money in one asset. Diversification spreads risk and increases the chances that at least some investments will perform very well. You might put some money in stocks (equities), some in fixed income (bonds or fixed deposits), some in property or land, some in your business or a startup, etc. In an African context, even investing in a cow or farming can be an asset – for example, a dairy cow produces milk you can sell (cash flow), plus more calves (growth). The key is these are productive uses of money versus letting cash sit idle.

-

Re-invest Returns: Whenever your investments pay you (interest, dividends, rent, profits), try to reinvest at least a portion of those gains. This accelerates your wealth growth. If you get dividends from NSE stocks or from your SACCO, for instance, consider buying more shares or re-depositing to earn even more next cycle. This compounding effect is how small sums grow huge over years.

-

Maintain an Emergency Fund (but not too large): You still need some savings readily accessible for emergencies – typically 3-6 months’ worth of expenses in cash or a liquid account. But beyond that, put your money to work. Don’t hoard excess cash out of fear. Educate yourself on investments so you feel more comfortable moving surplus savings into higher-return opportunities.

By transitioning from being just a saver to becoming an investor, you ensure that your money works as hard as you do. Over time, invested money can earn more money – a virtuous cycle that pure saving cannot achieve due to inflation and low interest. As the saying goes, “Don’t save what is left after spending; spend what is left after investing.” Prioritize growing your wealth, not just storing it.

Rule #3: Use Debt to Create Wealth (Not All Debt is Bad – Leverage It Wisely)

What this rule means: Debt is a double-edged sword – it can ruin finances if misused, but it can also be a powerful tool to accelerate wealth if used wisely. The rule here is to understand the difference between bad debt and good debt. Bad debt is borrowing to buy things that depreciate or consume (like gadgets, cars, or parties) – it keeps you poor. Good debt is borrowing to acquire assets that generate income or appreciate (like a rental property, a business, or education/skills that boost your income) – it can make you rich. The system doesn’t want you to know that the rich regularly use “other people’s money” (OPM) – i.e., leverage – to build their fortunes. Properly managed, debt can be used to buy investments now that you couldn’t afford outright, so you grow wealth faster than if you waited years to save up the full amount.

Mainstream vs. reality: Mainstream personal finance often paints debt with a broad brush: “Avoid debt, it’s dangerous.” Indeed, the average person’s experience with debt is negative – credit card balances, payday loans, and endless car payments that siphon their income. So the common advice is to become “debt-free.” However, the reality is more nuanced. Not all debt is created equal. The rich don’t completely avoid debt; instead, they avoid bad debt and aggressively employ good debt. For example, taking a loan to buy a rental house that pays you rent is very different from taking a loan to buy a flashy car that only costs you money. One adds to your income, the other adds to your expenses. As author Robert Kiyosaki (of Rich Dad Poor Dad) taught, “The rich use debt to leverage investments, while the poor use debt to buy liabilities.” The system doesn’t emphasize this difference.

In Kenya, think of it this way: If you borrow KSh 500,000 to purchase a piece of land in an area where property values are rising, that could be smart debt – in a few years the land might be worth far more, and you could sell or develop it for profit, paying off the loan and keeping the gain. But if you borrow KSh 500k to buy the latest Subaru Impreza to impress friends, the car’s value will drop and you’re left with a loan to pay from salary – classic bad debt. Reality: Debt, when used for buying appreciating or income-generating assets, can multiply your wealth. It’s how many businesses expand and how real estate investors acquire multiple properties. If the asset’s return is higher than the loan’s interest, you come out ahead. However, if you use debt for consumer spending, you’re on a treadmill of payments with nothing to show at the end.

Why the system wants you unaware: The financial system – especially lenders and credit providers – actually profits massively from bad debt. They want you to take loans, but not the kind that make you independent; they prefer you take consumer loans that keep you dependent. Credit card companies, mobile loan apps, and banks earn huge interest from people who carry credit card balances or use overdrafts for consumption. For instance, consider Kenya’s popular mobile loans: M-Shwari charges a 7.5% “facility fee” on a one-month loan (equivalent to ~90% annual interest), and the Fuliza overdraft charges about 1.083% per day – which is nearly 395% annualized interest! These products are marketed as convenience for users, but they trap many in a cycle of debt for everyday needs. The system definitely doesn’t advertise how to use debt to your advantage – they advertise how they can use your debt to their advantage. As evidence, banks and credit providers intentionally make consumer credit easy (one-click loans, credit card offers, buy-now-pay-later plans) because every time you borrow for consumption, they get richer through fees and interest. Meanwhile, they often make it harder for the average person to get “good debt” like a business loan or a mortgage for a rental (you face more scrutiny, need collateral, etc.). The less people know about leveraging debt for wealth, the more they’ll either fearfully avoid all debt (leaving wealth-building opportunities on the table for the rich) or misuse debt and become profit centers for lenders. Either scenario benefits the system: if you avoid debt entirely, you grow slower (staying in your place); if you drown in bad debt, you’re paying the system for life.

Kenyan/African examples: Many local examples illustrate good vs bad debt. A common one: SACCO loans vs mobile loans. SACCOs encourage members to borrow to invest – e.g., using a SACCO loan to buy dairy cows, farm equipment, or a plot of land. That loan is typically low-interest and tied to an asset that will generate income (milk sales, harvest yields, land appreciation). In contrast, app-based mobile loans (like Tala, Branch, Fuliza) are often used to pay for groceries or a night out when one’s salary runs short – and then next month’s income is already eaten by repayment. The former can increase your net worth; the latter just leaves you poorer with interest. Another example: entrepreneurs taking microfinance loans to buy stock for their shop or tools for their trade – that’s leveraging debt to increase business income. Compare that to someone perpetually financing the latest smartphone on credit. Clearly, understanding this rule is life-changing: it’s literally the difference between debt that makes you money and debt that breaks you.

Action Steps – How to Apply Rule #3:

-

Differentiate Good Debt vs Bad Debt in Your Life: Make a list of any debts you have or are considering. Label each as good or bad based on this simple test: Does this debt help me acquire an asset or increase my income? If yes, it’s potentially good (still needs to be well-managed). If it only funds consumption or a depreciating item, it’s bad. For example: a student loan for a marketable degree or a mortgage for a rental unit = could be good (investment in your earning power or an asset); a loan for a TV, wedding, or holiday = bad (you enjoy short-term, but pay long-term). Commit to eliminating bad debts and not taking new ones, while focusing on utilizing good debt strategically.

-

Leverage OPM (Other People’s Money) for Investments: If you find a promising investment but lack the full funds, consider financing it smartly. This could mean taking a bank loan, SACCO loan, or mortgage for an asset that will likely pay for itself. Key point: Ensure the numbers make sense. For instance, if you take a mortgage to buy an apartment to rent out, calculate that the rent minus expenses can cover the mortgage payment (or a large part of it). If yes, your tenant is essentially buying the property for you. If you borrow to expand a business, ensure the expected extra profits exceed the loan’s cost. In farming, if a loan lets you buy a tractor that lets you plow neighbors’ fields for a fee, the income from that tractor should ideally exceed the loan installments. Always do the math and have a buffer (what if interest rates rise or there’s a bad season?). If done prudently, using OPM can magnify your wealth – you reap 100% of the asset’s gains while only putting down a fraction of the money.

-

Avoid Predatory Loans and Credit Traps: Steer clear of the easily available high-interest debt that is designed to keep you in a hole. In Kenya that means things like mobile payday loans, high-interest shylock loans, expensive hire-purchase agreements, and credit cards if you can’t pay the full balance monthly. The staggering interest rates (90%+ APR on M-Shwari, ~400% on some short-term loans) are a quicksand for your finances. If you have any such debts now, prioritize paying them off as fast as possible (even before lower-interest loans) – they are essentially financial emergencies. Replace their use with better habits: build an emergency fund (so you’re not forced to borrow for emergencies), and live within your means (so you’re not borrowing for basics).

-

Use Cooperative & Lower-Cost Loans for Productive Purposes: If you do need to borrow, look for the lowest-cost sources and tie the loan to an investment plan. SACCOs often offer lower rates to members and even dividends that offset interest. For example, if a SACCO charges 12% on a development loan but pays you 8% dividend, your net cost might be 4%. Public institutions like the Higher Education Loans Board (HELB) offer student loans at subsidized rates to invest in education. Government programs or development funds sometimes provide affordable credit for SMEs or agriculture. Explore these for productive loans rather than grabbing the quick digital loan.

-

Have a Repayment Plan and Exit Strategy: Good debt can turn bad if mismanaged. Don’t take on a loan assuming everything will perfectly go right. Always ask “How will I repay this, even in a worst case scenario?” Have a plan B. For instance, if you take a mortgage for a rental property, could you still pay it if the tenant leaves for a couple of months? Maybe you need to keep a cash reserve or ensure dual incomes. If you use leverage in business, monitor the returns closely and don’t overextend. It’s wise to use debt in moderation – you can get burned by too much of even good debt if an economic downturn hits. Aim to eventually own the asset free and clear. For example, some people take a 5-year bank loan to buy a matatu, use the matatu’s income to pay it off in 3 years, and then they own an income-generating asset debt-free. That’s a smart use of leverage.

In summary, master the game of leverage but play it carefully. The rich grow faster by using other people’s money alongside their own, and you can too if you apply discipline. As a rule of thumb: Borrow for assets, never for liabilities. Let debt make you richer, not poorer.

Rule #4: Banks Are Not Your Friends – Understand How They Make Money Off You

What this rule means: Your bank may seem like a safe place to keep money or get financial advice, but remember this: banks are businesses, and their goal is to profit – often at your expense. The banking system is designed to use your money to make them money. They do this through practices like fractional reserve banking (lending out most of your deposits), paying you little interest while charging borrowers high interest, and layering fees on your transactions. Moreover, banks and credit card companies actively encourage financial behaviors that make them richer and you poorer, such as keeping you in debt or selling you products that aren’t truly in your best interest. This rule urges you to be skeptical of banks’ intentions, learn how the game works, and then use banks as tools (for transactions, credit when needed, etc.) – not as guides to your financial future.

Mainstream vs. reality: Many people grow up with a trusting view of banks: deposit your money and it’s just sitting safely, banks will advise you to help manage your finances, etc. The mainstream script says “open a savings account for security,” “the bank manager is your financial advisor,” and “debt is something you owe the bank so do whatever they say.” The reality is, banks operate on a model that profits from consumer ignorance. When you deposit KSh 100,000, the bank doesn’t lock it in a vault with your name; it likely keeps maybe 10% (KSh 10k) in reserve and loans out the other KSh 90,000 to someone else at high interest – this is fractional reserve banking. They might loan it to a business at 15% interest or issue credit card balances at 20%+, while paying you, say, 3% on your savings. Essentially, your money is being rented out by the bank. If you withdraw, they can use other depositors’ money or borrow from the central bank. This is legal and standard, but not widely understood by the public. Additionally, banks market credit cards and personal loans heavily because, as mentioned earlier, interest on those make up a big chunk of their profits. Credit card companies want you to carry a balance and pay only the minimum – that’s how they generate “insane profits” from interest and fees. Even the advice you get from a bank’s financial advisor or relationship manager is often biased: they might push certain investment funds or insurance because the bank earns a commission or fee from selling those to you. Reality: Your financial well-being is not a bank’s priority – their profit is. Once you accept this, you’ll handle your banking differently.

Why the system keeps you unaware: Quite simply, an uninformed customer is more profitable to banks. If you don’t know that your savings lose value to inflation, you’ll keep large balances in low-interest accounts (great for the bank, not for you). If you don’t understand how credit card interest accumulates, you might think a minimum payment is fine and stay in debt for years – a cash cow for the issuer. Many people don’t realize how many fees they pay (monthly account fees, ATM fees, mobile money transfer fees, etc.) because banks often bury it in fine print. The system also likes to project banks as pillars of trust – notice how in Kenya and many places, banks have fancy buildings and branding to appear secure and authoritative. This psychological play makes people less likely to question them. In truth, banks are not evil per se, but their incentives are to maximize what they earn from you. As the insider joke goes, a banker is someone who lends you an umbrella when it’s sunny and wants it back when it starts raining. Understanding this rule means you stop naively doing whatever your bank suggests and start thinking like a banker yourself.

Kenyan/African context: In Kenya, banks historically enjoyed hefty interest spreads and sometimes questionable practices. For example, for years banks here could pay minimal interest on savings (some accounts literally 0% interest for balances below a threshold) while lending to the government risk-free via Treasury bonds at high rates – essentially using depositors’ money to earn double-digit returns and giving depositors crumbs. Even now, the average lending rate is ~15% while savings rate is ~3-4%, as noted before. That gap is the bank’s margin. Another example: bank fees – some Kenyan banks until recently charged fees for almost everything (ledger fees, ATM withdrawals, balance inquiries). This would quietly eat away customer funds if they weren’t paying attention. On the flip side, a financially savvy person might buy shares of banks (like KCB or Equity) to “own the bank” and receive dividends from those big profits, rather than being just a customer. Mobile money (M-Pesa) and fintechs have also become quasi-banks, with their own fee structures. M-Pesa charges transaction fees that, if you use it heavily, add up to a lot – again profiting off convenience. If you are unaware, you might be paying hundreds of shillings monthly in fees that you could avoid or reduce.

A particularly egregious case: Overdraft facilities like Fuliza which effectively charges ~1% per day as mentioned. If a user doesn’t realize how expensive that is, they might keep “fuliza-ing” small amounts daily and wonder why their M-Pesa balance never seems to grow. The telecom and bank behind it (Safaricom and NCBA) are profiting immensely (Fuliza disbursed over KSh 1 trillion in digital loans by 2024!). This is why it’s critical to see the system for what it is.

Action Steps – How to Apply Rule #4:

-

Educate Yourself on Banking Practices: Knowledge is power. Take time to learn how banks actually operate. What is fractional reserve banking? How do banks use deposits? What fees and interest rates are you really paying? For instance, read your bank’s fee brochure – you might discover charges you didn’t know about. When you understand that for every KSh 1,000 you keep in a low-interest account the bank might be making 3x that by lending it out, you’ll be motivated to change. Also, learn about your rights – central banks and regulators often have consumer protection rules. In Kenya, the Banking Act and Central Bank regulations have rules on disclosure and fair practices. Be an informed client who can’t be easily taken advantage of.

-

Minimize Idle Cash in Banks: Keep only what you need for transactions and short-term needs in your regular bank account. It’s wise to maintain some liquidity for bills and emergencies, but any long-term savings or extra cash should be moved into higher-yield vehicles (as discussed in Rule #2). If you have a savings account, search for one that offers a competitive interest rate or use a money market fund as an alternative for parking cash. Some digital banks or fintech savings products give better rates. The less of your money sitting basically interest-free at a bank, the less the bank can use it for their profit without sharing.

-

Be Fee-Savvy: Little fees can silently rob you. Take note of every fee you’ve been paying – ATM fees, monthly account fees, mobile money transfer fees, cheque processing fees, etc. Then take steps: Can you switch to a bank account with no monthly fees? Many banks now offer “digital accounts” with zero monthly charges. Can you limit ATM withdrawals or use your bank’s own ATMs to avoid charges? For mobile money, can you reduce fees by sending fewer, larger transactions instead of many small ones (or use PayBill and merchant payments which sometimes have no fee for the sender)? Also, negotiate where possible: if you maintain a good balance, ask your bank to waive certain fees – they often will to retain a good customer. Over a year, saving KSh 300 a month in fees is KSh 3,600 that could be invested or pay other needs.

-

Don’t Take Bank Advice at Face Value: When a bank officer or any financial salesperson pitches you a product (insurance, investment fund, new loan, etc.), remember their incentive. Ask critical questions: “What are the charges? How does the bank benefit? Are there better alternatives in the market?” Feel free to compare with outside options – you don’t have to buy a bank’s unit trust, for example; you might find an independent fund with lower fees. If a bank is advising you to, say, refinance your loan or take a top-up, consider if it’s good for you or just good for them. Often they want to lock you into debt longer. Get a second opinion or do your own research, especially for major decisions like mortgages or large investments.

-

Think Like a Banker – Profit from the Bank: This is a mindset shift. Instead of always being on the paying side of the equation, see how you can be the bank. One simple way is to own bank stocks or SACCO shares. If banks are making huge profits from lending, owning a piece means you get a cut of those profits as dividends. Many Kenyan banks are listed on the NSE and pay decent dividends. For example, if Equity Bank or KCB posts big earnings (fueled by interest from borrowers), as a shareholder you benefit. Likewise, joining a SACCO makes you part-owner, and you earn dividends from the SACCO’s lending activities (some SACCOs pay over 10% dividends, essentially giving back profit to members). Another way to be the bank is peer-to-peer lending or lending within your community at fair interest (with proper legal structure) – essentially earning interest instead of paying it. Some Chamas operate like this: members contribute funds that are lent out to members or outsiders at interest, so the Chama members get the interest income, not a commercial bank. Obviously, one must manage risk (only lend what you can afford to tie up or potentially lose). The key is to position yourself on the side of earning interest whenever possible, not just paying it.

By treating banks as service providers you use (for safekeeping, transactions, credit when appropriate) – rather than benevolent caretakers of your money – you’ll make far better financial choices. Remember, understand the game and then use it to win. For example, if you know a bank is offering a “free” account but will pitch you a credit card, you’ll be ready to say no to the upsell. Or if you know your deposits help the bank make loans, you might negotiate better rates or move money elsewhere until they offer it. Be polite but firm in your dealings – you are the customer, and an informed customer can demand more value. In the end, don’t rely on banks to make you rich; rely on yourself, using banks as one tool in your financial toolbox.

Rule #5: Financial Education is Your Responsibility (Schools Won’t Teach You Wealth)

What this rule means: You must take charge of your own financial education because the formal education system will not give you the knowledge needed to become wealthy. This rule is about proactively learning how money works – budgeting, investing, taxes, entrepreneurship, etc. – from books, mentors, real-world experience, and resources like this blog. Traditional schools (from primary to university) often completely omit personal finance and wealth-building topics. If you don’t actively seek this knowledge, you’ll graduate knowing how to solve calculus or recite history dates, but not how to manage debt, invest in stocks, or build passive income. The system doesn’t want a populace that’s financially savvy and independent, as it would upset the labor-consumer balance. Thus, to get ahead, you have to become financially literate on your own – it’s an “extra-curricular” life project that pays huge dividends.

Mainstream vs. reality: Mainstream thinking assumes that if you do well in school and get a good job, that’s enough for financial success. We often equate being educated (academically) with being good with money, but they are very different skill sets. You probably know of highly educated people – even those with MBAs or PhDs – who still struggle with debt or live paycheck to paycheck. That’s because traditional education doesn’t cover real-world money skills. The reality is stark: studies have found low levels of financial literacy worldwide. For example, only about 38% of Kenyan adults are financially literate according to a global survey, meaning the majority cannot answer basic questions on inflation, interest, and risk diversification. It’s not their fault – these concepts were never taught in school. Instead, many of us grew up hearing “money is the root of all evil” or “just work hard and money will follow,” without learning how to make money work for us. Reality is that understanding money is as important as earning it. If you hand someone KSh 1,000,000 who lacks financial education, chances are they’ll lose or waste it; give a financially savvy person the same amount, they’ll likely grow it. The system, intentionally or not, leaves a knowledge void that you must fill.

Why the system wants you unaware: A population that’s financially illiterate is easier to shepherd into roles that benefit the system (as workers and consumers). Think about it: if schools taught every child how to invest in stocks, how to evaluate insurance, how to start a business, how debt works – the average person would be much harder to exploit. They might demand higher pay (knowing the value of their labor), they might avoid harmful loans, they might compete with established businesses by starting their own. There’s a cynical saying: “They don’t teach you money in school because they want you to work for money, not have money work for you.” Whether by design or by oversight, the end result is the same – a lack of early financial education means young adults enter the workforce prey to credit card offers, impulsive spending habits, and investment scams, because they simply weren’t trained otherwise. The system benefits as follows: corporations get a compliant consumer who buys on emotion rather than financial sense, banks get a borrower who didn’t learn the dangers of compound interest on debt, and employers get someone who doesn’t know how to achieve financial independence and thus will stick around working for decades. If instead people were widely taught how to achieve financial freedom, many would opt out of exploitative systems and be more independent. To be clear, some efforts are being made by progressive schools or initiatives to include financial literacy, but it’s not yet widespread or sufficient. In Kenya, only recently have organizations started introducing financial literacy content into the school curriculum, which means older generations got none of it. So if you want to be financially successful, you cannot rely on formal education or society’s default teachings – you have to self-educate in money matters.

Kenyan/African context: Culturally, talking about money at home has sometimes been taboo, and schools reinforced that silence by not teaching it. Many African youths first learn about money by making mistakes – perhaps falling for a get-rich-quick scheme, misusing a HELB loan refund, or blowing their first salary because they never learned budgeting. For example, a Kenyan graduate might start earning and suddenly be bombarded with “deals” – from shady pyramid schemes to peer pressure to finance a lavish lifestyle – without a foundation to discern what’s smart financially. Meanwhile, someone who somehow got financial education early (maybe from a mentor or reading) might invest part of their salary in a side business or stocks and get ahead. We also see well-meaning but misinformed advice passed down: e.g., some parents might urge “buy land at all costs” or “go for the highest paying job” without nuance – which isn’t always the best holistic strategy if it leads to liquidity issues or burnout. The point is, modern personal finance is a skillset that many of our parents and teachers didn’t have themselves, so we must obtain it elsewhere.

Action Steps – How to Apply Rule #5:

-

Commit to Ongoing Financial Learning: Make a personal commitment that you will continuously educate yourself about money. It’s not a one-time thing, but a lifelong learning process. Start with basics: understand budgeting, saving, and debt management, then advance to investing, economics, and wealth-building strategies. There are plenty of resources to help: books (e.g., Rich Dad Poor Dad by Robert Kiyosaki – great for mindset; The Richest Man in Babylon by George Clason – great for basics; or local personal finance books/blogs by African authors for context), blogs and websites (like Global Wealth Insights!), YouTube channels (Jaspreet Singh of Minority Mindset, Kenyan YouTubers like Money Coach, etc.), podcasts, and even free courses. Dedicate at least a few hours each week to learning about finances. Over a year, this will dramatically increase your knowledge.

-

Learn from Mentors and Peers: Identify people in your community or network who are financially savvy and observe or ask for advice. This could be a relative who runs a successful business, a colleague who seems to invest wisely, or a local “self-made” entrepreneur. Most people are happy to share knowledge if you ask respectfully. For instance, if there’s someone in your church or neighborhood known for real estate investments, consider approaching them: “I’m trying to learn more about investing – do you have any tips or resources you recommend?” Many villages and towns have chama elders or SACCO managers who have a wealth of practical knowledge – interact with them. Surrounding yourself with at least a few people who have a healthy financial mindset will rub off on you.

-

Use Local and Online Financial Literacy Programs: In Kenya, there are growing initiatives for financial education. For example, some banks run free clinics or seminars on money management; NGOs and Saccos sometimes host workshops. Organizations like Kenya Bankers Association and FSD Kenya produce materials on financial literacy. Take advantage of these. Also, consider formal short courses – e.g., Strathmore University and others have personal finance programs (if affordable or if you can get a scholarship). Online, you can find courses on Coursera or EdX about personal finance basics at low or no cost. The idea is to treat financial learning as seriously as professional learning.

-

Practice What You Learn (Start Small): Knowledge without action is not very useful. Start applying lessons in real life as soon as possible, even on a small scale. If you learn about stocks, maybe try buying a small amount of shares through a broker or the Kenyan digital trading apps to get a feel. If you read about budgeting, immediately implement a simple budget for next month. Learning about compound interest? Perhaps try out a money market fund with a bit of money to see how interest accrues monthly. Experience cements learning and also reveals gaps or additional questions, which you can then learn about. Don’t worry about making everything perfect – small, low-risk trials are great for learning. It’s better to make a KSh 5,000 investment mistake at age 25 and learn from it than to be clueless with KSh 5,000,000 at age 50.

-

Teach and Discuss Money: One of the best ways to solidify your financial knowledge is to teach others or at least discuss it. This breaks the taboo and also reinforces your understanding. You could form a small group with friends where you discuss money topics monthly – like a book club but for finance. Or talk to your spouse and family openly about financial plans and what you’re learning (age-appropriate talks with kids too). By explaining concepts to others, you’ll identify areas you need to clarify for yourself. Also, advocating for financial education – for instance, pushing for inclusion of personal finance in school curricula or community programs – not only helps society but keeps you engaged with the material. Remember, you want to become the person who knows how to handle money so well that others eventually seek your advice – that’s a good sign you’ve mastered financial literacy.

In summary, don’t outsource your financial education. The cavalry isn’t coming – not the schools, not the government. But the resources are all around you if you seek them. The more you learn, the more you earn (or save). By empowering yourself with financial knowledge, you break the cycle that the system perpetuates, and you can then make optimal decisions in all other rules we discuss. You’ll see through scams, avoid traps, and seize opportunities that others might miss. Knowledge truly is wealth in the making.

Rule #6: Live Below Your Means and Avoid the Consumer Trap (Consumerism Keeps You Poor)

What this rule means: In an age of flashy lifestyles and relentless advertising, it’s crucial to spend less than you earn and funnel the difference into investments. Living below your means – essentially avoiding lifestyle inflation and unnecessary spending – is a fundamental rule for building wealth. The “consumer trap” refers to the cycle of earn -> spend it all (or more, via credit) -> repeat, which leaves people perpetually broke no matter how much they earn. The system encourages constant consumption: new gadgets, trendy clothes, eating out, the latest car model, etc. If you follow that script blindly, you’ll never accumulate capital to invest. Meanwhile, the rich often live relatively frugally and spend strategically on things that grow their wealth. By resisting consumerism and practicing delayed gratification, you free up money to save and invest, which is the only way to get ahead financially.

Mainstream vs. reality: The prevailing culture (fueled by marketing and social media) often equates spending with success. When you get a raise or windfall, the expected behavior is to “upgrade” your lifestyle – move to a bigger house, get a nicer car, celebrate with an expensive vacation. Many people follow a 50-30-20 budget rule or similar (50% needs, 30% wants, 20% savings), but in practice they end up with 0% savings because wants easily expand. Mainstream advice does tell people to budget, but the reality is that consumer pressures are immense. The reality of wealth-building is almost boring: spend significantly less than you make, and invest the rest, consistently, over years. It’s how a teacher earning KSh 50,000 can retire richer than a doctor earning KSh 200,000 who spends lavishly. As Warren Buffett famously exemplifies – he still lives in a modest house he bought in 1958 despite being one of the richest men – wealthy people often don’t look wealthy. They aren’t necessarily buying the latest designer clothes or 2025 Mercedes; they’re more focused on growing their asset base. Conversely, plenty of people driving luxury cars or wearing expensive shoes have huge debt or no savings. “All that glitters is not gold.” The reality is that frugality and conscious spending are virtues on the path to financial freedom. It doesn’t mean being stingy or never enjoying life; it means not letting your expenses rise as fast as your income, and not buying things to impress others at the cost of your future.

Why the system wants you unaware: Consumer spending is the lifeblood of the economy. Governments track GDP growth, and a big component of GDP is consumer expenditure. Businesses need you to keep buying their new products. If too many people suddenly decided to live below their means and cut frivolous spending, many industries would shrink. So there’s a massive engine encouraging you to spend: advertising (telling you that you “need” that new phone upgrade or that your life will be better with product X), easy credit (so you can buy now and pay later), and social pressure (seeing peers on Instagram living it up creates FOMO – fear of missing out). The system benefits in multiple ways when you overspend: companies make profits, the government collects more VAT and sales taxes on your purchases, and banks earn interest if you borrow to spend. Additionally, if you’re always spending everything, you remain one paycheck away from broke, which keeps you dependent on your job (good for employers) and with little bargaining power. In contrast, if you have a year’s worth of savings and investments, you can afford to say no to a bad job or take entrepreneurial risks. The system doesn’t want a populace that can “walk away” – they want you tethered to the next paycheck. Thus, society (via media and norms) celebrates visible consumption (the latest smartphone, fancy weddings, new cars) but rarely applauds someone for living frugally. That’s intentional: a disciplined consumer is bad for short-term business. But as your strategy, living below your means is fantastic for you.

Kenyan/African context: The consumerism trend is very visible in African cities now. Walk around Nairobi or Lagos and you’ll see the allure of the high life – billboards for luxury apartments, everyone posing with the newest iPhone, the culture of “no expense spared” social events (grand weddings, dowry ceremonies, etc.). Meanwhile, traditional wisdom in many African cultures was actually more frugal – our grandparents often lived simply and saved for a rainy day. But with modernization, many youth fall into debt trying to keep up appearances. Consider the rise of buying goods on credit or using digital loans to fuel lifestyle: some young professionals routinely use Fuliza or credit cards to eat at expensive restaurants or wear imported fashion, essentially financing a lifestyle they can’t afford. That’s a trap. Another example: Car loans have become common – someone will take a huge loan to buy a car that is more of a status symbol than necessity, then struggle with monthly payments (and fuel, maintenance) that eat half their salary. On the flip side, I know of Kenyan investors who still drive a basic Toyota or no car at all, but quietly acquire plot after plot of land with their surplus money – a few years later, the flashy car owner has a depreciated vehicle, while the frugal investor has land that doubled in value. Additionally, we have cultural pressures like harambee (fundraisers) or extended family obligations that can strain finances – it’s important to balance generosity with personal financial limits, otherwise you end up sacrificing your own financial stability (you can’t help others if you bankrupt yourself). Ultimately, avoiding the consumer trap in Kenya might mean resisting the urge to “acha nionekana” (appear successful) while secretly building your wealth.

Action Steps – How to Apply Rule #6:

-

Track and Trim Your Expenses: Start by creating a simple budget or expense tracking system. List all your monthly expenses – you might be surprised where your money is actually going. Apps like Mint, Money Manager, or even a notebook or spreadsheet can help. Once you see the breakdown, identify areas to cut back without significantly affecting your happiness. Often there is waste: unused subscriptions (that Showmax or DSTV package you rarely watch), frequent takeout coffees and lunches, or high utility bills that could be reduced with conservation. Trim the fat and redirect that money to savings/investment. For example, if you find you spend KSh 5,000 a month on lunches at work, consider meal-prepping and cutting that in half – that’s KSh 30,000 a year freed.

-

Avoid Lifestyle Creep: Each time your income increases (bonus, raise, new income stream), resist the automatic impulse to upgrade your lifestyle proportionally. A good rule of thumb is to save or invest at least 50% of any increase in income. So if you get a raise of KSh 10,000 a month, commit KSh 5,000 or more of that to your investment account before you even feel it. Of course treat yourself a little – maybe 10-20% of the raise – but bank the rest. This way, your lifestyle improves slowly and sustainably, and your wealth grows much faster. Many people in Nairobi fall into the trap of moving to a much pricier apartment or buying a fancy car as soon as their pay goes up, leaving them no better off financially. Don’t be that person. Upgrade only when truly necessary, and even then, as modestly as you can. For instance, you might choose to stay in your current affordable neighborhood an extra year or two and use the extra money to buy a plot back in your home county (an investment), rather than rent a high-end place in Kilimani that leaves you asset-poor.

-

Embrace a Value Mindset, Not a Show-off Mindset: Reframe how you think about spending. Before making a purchase, especially big ones, ask: Is this providing real value to my life or is it just an impulse or status purchase? This doesn’t mean never buy nice things – it means buy what you truly value and what you can afford comfortably. If you love photography and an expensive camera brings you joy and maybe side income, that’s more justified than buying the latest phone just because others have it. Practice waiting before buying (the 30-day rule for big buys: note it down, wait 30 days, see if you still want it). Often the urge will pass, and you’ll save money. Also, find joy in free or low-cost activities: exercise, reading (library or online resources), spending time with family, exploring nature – these improve life without draining your wallet. When you do spend on wants, try to get the best deal – shop during sales, negotiate (common in markets here), or buy quality used items instead of new. For example, buying a fairly new second-hand car in cash is far smarter than a brand new one on loan; the used one is cheaper and won’t depreciate as heavily.

-

Use the “Pay Yourself First” Principle: One practical method to enforce living below your means is to automate your savings/investments as soon as you receive income. This is often called “paying yourself first.” For instance, if you decide 20% of your income should go to investments, set up a standing order or automatic transfer on payday that moves that 20% into a separate investment or savings account (or SACCO deposit, etc.). What’s left in your main account is what you live on. Human psychology adjusts to what’s available, so you’ll naturally budget the remainder better. By removing the investment portion first, you ensure you don’t accidentally spend it. Many employers can direct-deposit a portion of salary to a savings account or pension – use those facilities. Over time, try to increase the percentage you pay yourself first – challenge yourself to go from 10% to 15% to 20% or more. Some very ambitious savers in the FIRE (Financial Independence, Retire Early) movement save 50%+ of their income. Even if that’s not feasible for you, any increase accelerates your path to wealth.

-

Cultivate Contentment and Long-Term Thinking: This is the mindset part – train yourself to derive satisfaction not from immediate purchases but from watching your investments grow and knowing you’re building a solid financial foundation. It can actually become addictive in a good way: seeing your SACCO shares earn dividends, or your stock portfolio rise, can give you a dopamine hit similar to buying a new gadget, but with lasting benefits. Keep visual reminders of your goals – maybe a picture of the plot of land you want to buy or an amount you aim to have invested – so that when tempted to splurge, you recall what you truly want long-term. Also, choose your social circle wisely; spend time with people who have similar financial discipline or who encourage your goals, not ones who pressure you to overspend. In Kenya, peer pressure can be intense – e.g., friends insisting on expensive outings. It’s okay to say “That’s out of my budget this month, how about we do X cheaper activity instead?” True friends will understand, and you might even influence them. Over time, as your wealth grows, you’ll be able to afford many of your dreams comfortably – but by then you might find you’re happier living simply with financial freedom than living large with financial stress.

By living below your means now, you create the gap (savings) that is necessary to fund all the investing and wealth-building mentioned in the other rules. It might require bucking societal trends and delaying some gratification, but the reward is that you won’t be one of the 70% who are broke at month’s end. Instead, you’ll watch your bank balance and investments swell year by year, and that gives you options – maybe to retire early, to handle emergencies with ease, or to seize a business opportunity when it comes. As the proverb goes, “If you buy things you don’t need, soon you will have to sell things you need.” Avoid that fate by mastering your consumer impulses. Your future wealthy self will thank you.

Rule #7: Own Assets, Not Just Stuff – Build Multiple Streams of Income

What this rule means: The final rule ties many of the previous ones together: focus on accumulating assets and creating multiple income streams, rather than just working for a paycheck and buying “stuff.” An asset is something that puts money in your pocket, either via appreciation or income generation. Examples: stocks, bonds, rental properties, businesses, farms, intellectual property, etc. “Stuff” or liabilities, on the other hand, take money out of your pocket (a car can be a liability – fuel, maintenance, depreciation – unless it’s an Uber car earning you money; a fancy TV is just consumption). To achieve financial freedom, you need to own a portfolio of assets that generate enough passive (or semi-passive) income to cover your needs. Relying on one income source (like a single job) is risky and limiting. The wealthy usually have their money coming from many directions – salary, business profits, rental income, dividends, interest, royalties, etc. Each additional income stream is like a pillar supporting your financial house. If one weakens, others hold up. The system doesn’t encourage you to think like an owner; it prefers you remain a consumer and maybe a wage-earner. But by intentionally acquiring assets and nurturing multiple incomes, you switch to the wealthy playbook.

Mainstream vs. reality: The mainstream path for a lot of people is: get a job, maybe eventually buy a house (which they often mistakenly count as an asset, even though it doesn’t pay them unless they rent part of it out), and possibly contribute to a pension. Nothing wrong with that, but it’s a slow road and often insufficient. Reality in today’s world is that job security is not guaranteed, pensions can be inadequate (or non-existent by the time younger folks retire, especially in countries where social security systems are strained), and inflation can erode saved money. The average millionaire reportedly has 7 streams of income – whether that exact number is true or not, the point is multiple flows of money provide resilience and growth. If you look at rich individuals in Africa: a person might have a corporate job and own a matatu fleet and some rental apartments and a farm back home and stocks. They didn’t rely on just one thing. Meanwhile, someone who works 9-5 and spends the rest of time relaxing could be stuck on one income forever. The reality is also that assets do the heavy lifting of wealth creation. A shamba (farm) left alone still grows crops you can sell; your stock shares earn dividends without you; your rental brings rent while you sleep. As you accumulate these assets, your need to personally work for money decreases – that’s the path to financial freedom. But if all you own are depreciating goods (car, electronics, clothes) and you have only your salary, you’re one job loss or one mishap away from crisis, and you cap your wealth at whatever you can personally earn.

Why the system wants you unaware: The system (like corporations and even some governments) would prefer you to be a dependent worker, not an independent owner. If too many people become self-sufficient via assets, who will do the work? There’s almost a subtle discouragement of having “side hustles” or other income in some corporate cultures – they want all your focus on the job. Some employers even have clauses preventing you from running a business on the side. That’s because a workforce that has no alternative income will comply more and accept whatever wage is offered. Also, if you don’t accumulate assets, you’ll pour your income into consumption (good for the economy as noted) and into banks via loans (if you’re buying stuff on credit). There’s also a bit of “fear” sold around certain asset classes – e.g., the stock market is “too risky” for regular folks (so just leave your money in the bank or a low-yield account), or starting a business is “too hard.” These fears keep people from even trying, leaving more asset ownership to big players. Consider land: in some places, large companies or wealthy families hold huge land assets while common folks rent – partly because ordinary people were never educated or encouraged on how to acquire land. In Kenya, we do have a culture of land ownership fortunately, but now even things like stocks or government bonds are areas many average people shy from, thinking it’s only for the rich or experts (which isn’t true – anyone can start with small amounts). The system doesn’t come out and say “don’t own assets,” but it distracts you with consumption and job-centric life so you forget to invest. It’s up to you to break out of that and say: Every year, I will add at least one new asset to my name.

Kenyan/African context: We have unique opportunities and examples here. In Kenya, one popular asset-building avenue is buying land/home plots (even if just a small plot upcountry, it’s yours and often appreciates). Also, participating in Chamas or investment groups allows people to co-own assets they couldn’t afford alone – e.g., a group of 10 friends might each contribute monthly and eventually buy an apartment to rent out, splitting the income. There are stories of office colleagues forming a chama that ends up owning a whole apartment block after several years – those colleagues created an extra income stream (rent) outside their salaries. Another modern avenue: digital assets and online income. For instance, a Kenyan might start a YouTube channel or blog (like this one) which over time generates advertising revenue – that’s an income stream from intellectual property. Or one could develop an app or write an e-book that sells. These are assets too. Agriculture is another – a small scale farmer who diversifies into say poultry, dairy, and crops has multiple income streams on their farm. Compare that to someone who just relies on employment: if that person loses the job, income drops to zero. The farmer or the asset-owner still has others. Real case: during COVID-19 job losses, those who had side businesses or rental income weathered the storm better than those who only had a salary which vanished. It underscored the importance of not putting all eggs in one basket.

Action Steps – How to Apply Rule #7:

-

Identify or Create One New Income Stream at a Time: If you currently rely on only one income, brainstorm ways to add another. It could be something small to start – the key is to get the ball rolling. Maybe you have a hobby or skill that can be monetized (e.g., photography, baking, coding). You could do freelance gigs or sell products related to that. Or consider an investment that yields income: could you afford a vending machine to place somewhere? Could you invest in a matatu or boda boda and hire a rider/driver? Or put some money in a dividend-paying stock or a REIT (Real Estate Investment Trust) that gives you periodic payouts? Pick one idea that’s feasible and take action on it. Once it’s up and running, you can think of another. Don’t overwhelm yourself trying to do ten things at once; build steadily. Over a few years, you could have 3–5 different income sources blooming.

-

Reinvest Income to Acquire Assets: Use the “snowball” approach. When your new income streams or investments pay you, reinvest a significant portion of those earnings into more assets. For example, if you start a small side hustle selling goods on Jumia and it nets you KSh 10,000 a month, use that money to maybe buy some shares, which then give dividends or appreciate. Or use it to make a down payment on a plot of land (coupled with savings). Likewise, if your SACCO dividends arrive, instead of spending them, perhaps buy more SACCO shares or use them to partially finance another project. Reinvestment is how the rich keep growing their wealth – they don’t withdraw and blow all the profits; they deploy them to generate more income. Of course, treat yourself occasionally, but keep the big picture.

-

Diversify Across Asset Types: Aim to own a mix of asset classes for resilience. In Kenya, good categories include: Real Estate (land, rental units, even AirBnB property if in a city), Equities (shares of companies via NSE or even foreign markets ETFs for global diversification), Fixed Income (Treasury bonds – which pay interest every 6 months, or high-yield corporate bonds if available, or even a fixed deposit in a Sacco which is like a bond), Business equity (either your own business or investing in someone else’s enterprise), and possibly Agriculture or Commodities (like livestock – a few cattle or goats can be seen as assets, they breed and provide products like milk). Each has its pros/cons, but by spreading out, you ensure one market downturn doesn’t wipe you out. For instance, stocks might be down one year but your rental income still comes, or crop prices fall but your bond interest is fixed. Diversifying income streams goes hand in hand with diversifying assets.

-

Think in Terms of Ownership and Equity: Whenever you engage economically, consider if there’s a way to get an ownership stake rather than just a one-time payment. Example: If you’re providing a service or labor, could you negotiate to get a percentage of profits or shares instead of (or in addition to) salary? Some startups offer equity to early employees – which can be lucrative if the company grows. If friends are starting a business and you have some money, maybe you invest as a silent partner. When you buy a house to live in, could you buy a duplex and rent the other unit (so you own property and it generates rent)? This thinking ensures you’re always adding to your asset column. Even with personal items – you buy a camera for fun, maybe occasionally rent it out to someone who needs it for a shoot. Owning assets that have potential to earn is the mindset.

-

Periodically Review and Adjust: As you start building multiple streams, periodically (say yearly) review how each is performing. You might find one stream outperforms and deserves more focus, while another is too much effort for little return (you can cut it or sell that asset). Also review if you are too concentrated in one area – e.g., if all your income streams are related (say you have three small businesses all dependent on the tourism sector, or multiple rental properties in the same locale) you might want to diversify risk by adding a different type. Keep an eye on economic trends too: if interest rates go up sharply, bonds and fixed income might become more attractive; if stock market is down, maybe it’s a chance to buy more shares cheap. Being an asset owner means being a capital allocator – decide where your money goes for best effect. It’s an ongoing strategy game, but one that becomes enjoyable as you see progress.

By following this rule, you essentially graduate from being just an “income earner” to a “wealth builder.” Every asset you acquire is like hiring an employee that works for you 24/7 to make money. The more of these mini-employees (assets) you have, the less you need to physically work yourself. Over time, your multiple streams of income could even exceed your expenses by far – at that point, congratulations, you’re financially independent! You can choose to work or not, and you’ve insulated yourself from many of life’s uncertainties. That is the ultimate goal that the system never teaches you – but now you know the rule. Start putting it into practice, one asset at a time.

Conclusion:

You’ve now learned the seven money rules the system doesn’t want you to know: (1) Don’t rely solely on a salary – stop trading time for money; (2) Don’t just save, invest your money so it grows; (3) Use debt wisely as leverage for wealth, avoid debt traps; (4) Recognize banks’ incentives – they profit from your ignorance, so be informed and make them work for you; (5) Take charge of your financial education, since schools won’t teach it; (6) Live below your means and resist consumerism to free up wealth-building capital; (7) Own assets and build multiple income streams to secure your financial future. These rules break from the mainstream script and that’s exactly why they work – by doing what most people won’t, you can achieve results most people don’t.

Each rule addresses a way that “the system” keeps people ordinary and exploitable, and flips it to empower you. By understanding the rationale behind each rule, you also see how the system benefits when you remain unaware – whether it’s your bank enjoying profits from your inertia, or consumer companies riding on your impulse spending. But now you’re aware. Remember, knowledge without action is meaningless. The power of these principles lies in applying them consistently in your life.

Start today: pick one or two rules that resonated most and take a concrete step – maybe it’s opening that investment account, or drafting a budget that cuts needless spending, or signing up for a finance course, or talking to a mentor. Small steps compound into huge leaps over time. Your journey to financial freedom is a marathon, not a sprint, but every shilling put to work and every smart choice puts you miles ahead of where you’d be otherwise.

Importantly, this journey is not just about becoming rich; it’s about freedom, security, and the ability to live life on your own terms. It’s about not lying awake stressed about bills, about having the means to support family and community, and about pursuing your dreams instead of being trapped in the rat race. In the African context, financial empowerment can uplift entire families and communities – you could be the catalyst that breaks generational cycles of poverty or financial illiteracy in your lineage.

As you implement these rules, stay motivated and patient. There will be challenges – maybe a bad investment or pressure to conform to old habits – but keep the bigger picture in mind. You are fundamentally changing your money mindset to that of the minority who succeed. Over time, you’ll see the payoff: maybe in a few years you buy that home outright while peers struggle with loans, or you have a thriving side business, or your investment portfolio’s passive income covers your rent.

We encourage you to share what you’ve learned with friends and family. Spark conversations about money rules at your next chama meeting or family gathering. You might be surprised how many others are eager for this knowledge (remember that statistic – majority are not financially literate, so you can be a beacon). By spreading financial literacy, you’re not only helping others but also reinforcing your own understanding.

Finally, as part of our Global Wealth Insights community, remember that you’re not alone on this journey. We regularly publish tips, guides, and success stories to keep you informed and inspired. Subscribe to the Global Wealth Insights blog (if you haven’t already) to get our latest articles and updates straight to your inbox. By subscribing, you’ll ensure you continue receiving valuable insights on growing wealth, specifically tailored to Kenyan and African contexts, and you won’t miss out on new opportunities and strategies as they emerge.

Recap of the 7 Money Rules: Work smarter (not just harder) for money, invest instead of just saving, leverage good debt, be savvy with banks, self-educate on finances, spend below your means, and accumulate assets for multiple incomes. These rules are your blueprint to financial freedom. Tape them to your mirror, make them your mantras, and refer back to this guide whenever you need a refresher or dose of encouragement.

You have the power to transform your financial destiny. No matter your starting point – whether you’re a recent graduate, a mid-career professional, or an entrepreneur – implementing these rules can set you on a path to prosperity. The system may not want you to know these secrets, but now you do. It’s time to use them and become the architect of your own wealth story.

Thank you for reading! We hope you feel motivated and empowered to take charge of your finances. If you found this guide helpful, do let us know and share it with others. And be sure to hit that subscribe button for more Global Wealth Insights – together, let’s build a financially free and prosperous future!

What's Your Reaction?