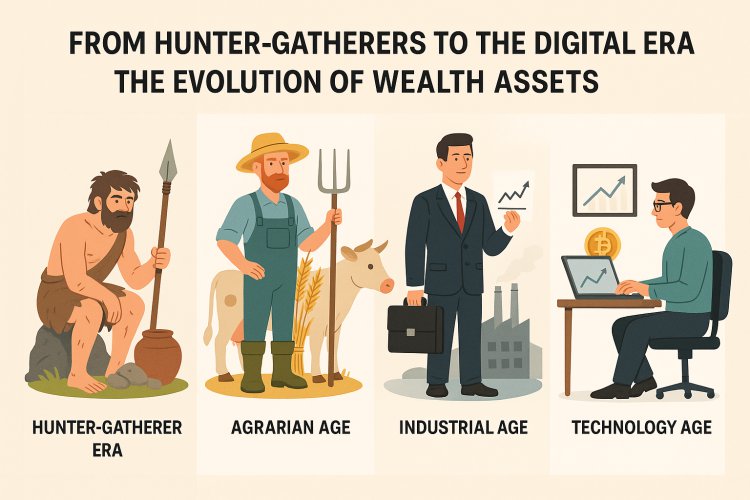

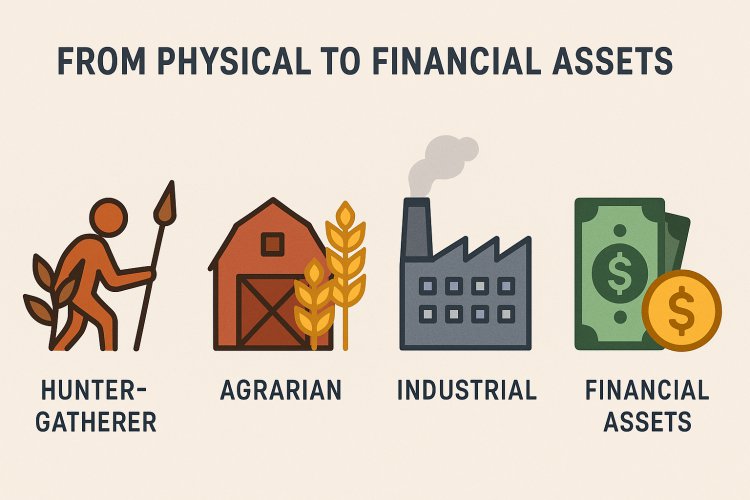

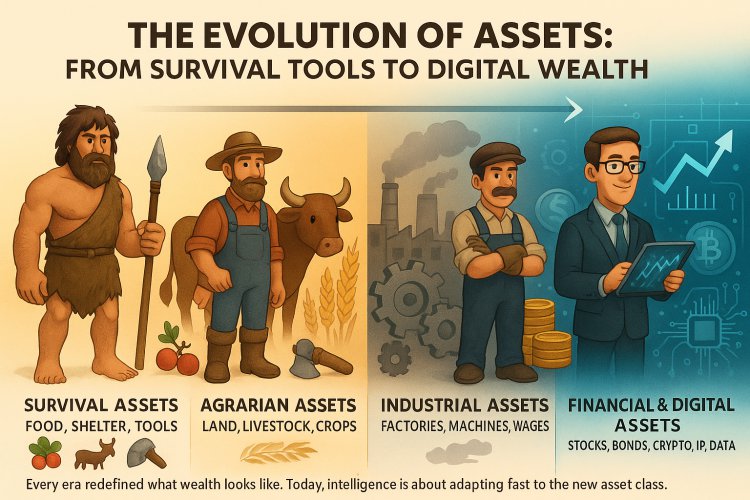

From Hunter-Gatherers to the Digital Era: The Evolution of Wealth Assets

Humanity’s definition of wealth has changed dramatically—from the tools of hunter-gatherers to farmland and livestock in agrarian times to factories in the industrial era and now to financial and intangible assets in the technology age. This article explores the transformation of assets across history, highlighting the advantages, disadvantages, and global perspectives of moving from physical to financial wealth. It also reveals what this shift means for modern individuals seeking to build and protect wealth in today’s fast-changing economy.

Human economic systems have undergone dramatic transformations—from small bands of hunter-gatherers to vast global digital economies. Along the way, the concept of wealth and preferred assets has continually shifted. In early eras, wealth was tangible: fertile land, herds of livestock, or a stockpile of tools and food. Today, much of the world’s wealth is held in intangible or financial assets—stocks, bonds, cryptocurrency, intellectual property, and the like. This article explores four major economic stages (hunter-gatherer, agrarian, industrial, and technology ages) and how each defined what people valued as assets. It also examines why society moved from physical to financial assets, the benefits and drawbacks of this shift, and what this evolution implies for building wealth in the modern world.

The Hunter-Gatherer Era: Subsistence and Minimal Assets

In the prehistoric hunter-gatherer era, humans survived by foraging and hunting. They were nomadic, owning very few possessions. Wealth was largely immediate and communal—the day’s catch or harvest shared within the tribe. Tools and knowledge of the environment were the most valuable “assets.” Social bonds were also crucial; the tribe itself functioned as a form of security.

There was little concept of private property or wealth accumulation. Everyone had roughly equal status, with no permanent economic classes. Wealth was essentially the bounty of nature and the skills to access it.

The Agrarian Age: Land as the Source of Wealth

The advent of agriculture transformed wealth. Humans settled, domesticated plants and animals, and produced surpluses. Land became the foundational asset of agrarian societies. Those who controlled fertile land gained food, income, and power. For centuries, landownership was the primary measure of wealth.

Classes emerged: landowners (royalty, nobility, and chiefs) amassed estates, while peasants worked the land. Livestock became another critical store of value. In many cultures, cattle or gold jewelry was seen as portable wealth. Early forms of money also appeared to ease trade.

The agrarian age entrenched social hierarchies, as control of physical assets concentrated in fewer hands. Land, livestock, crops, and tools were the dominant assets of this era.

The Industrial Age: Capital, Machines, and Financial Assets

The Industrial Revolution shifted wealth from land to industrial capital. Factories, machines, railroads, and infrastructure became the engines of prosperity. A new urban middle class arose, while the dominance of the landowning aristocracy declined.

Crucially, this era saw the rise of financial markets. To fund massive industrial projects, entrepreneurs sold stocks and bonds. Shares in companies became valuable assets themselves. Banking and national currencies matured, and wealth increasingly included savings, pensions, and securities.

By the late 19th century, owning companies and capital was as important as owning land. Wealth broadened from physical property to include financial claims on productive enterprises.

The Technology Age: Intangible Assets and Digital Wealth

The late 20th and 21st centuries ushered in an economy driven by knowledge and technology. Value now lies in intellectual property, data, software, and brand strength. Many of today’s most valuable companies hold relatively few physical assets; their worth comes from code, patents, or network effects.

Corporate balance sheets reflect this shift: intangible assets now account for the vast majority of value in leading firms. For individuals, wealth increasingly means holding financial assets (stocks, bonds, funds) and creating intellectual property (apps, content, patents).

New asset classes such as cryptocurrencies have emerged, purely digital and global. Finance has also become more accessible: mobile banking and online platforms let anyone with a phone start investing. Still, physical assets like real estate remain important, though often financialized through instruments like REITs or mortgages.

(Visual idea: A pyramid diagram showing the base as land/resources, the middle as industrial capital, and the top as intangibles/financial assets.)

Benefits of the Shift

-

Liquidity: Financial assets can be traded quickly, unlike land or machinery.

-

Diversification: People can spread wealth across multiple assets, reducing risk.

-

Accessibility: Ordinary individuals can invest in enterprises and markets.

-

Innovation & Growth: Financial systems channel savings into productive ventures.

-

Global Reach: Capital can flow internationally, funding projects worldwide.

-

Intangible Value Creation: Education, innovation, and IP drive growth and improve living standards.

Drawbacks of the Shift

-

Volatility: Financial assets can lose value rapidly during market crises.

-

Complexity: Modern finance is difficult to navigate without literacy and guidance.

-

Inequality: Wealth often concentrates among those with access to financial assets.

-

Speculation: Finance can detach from real economic value, creating bubbles.

-

Systemic Risk: Interconnected markets spread crises quickly.

-

Fragile Intangibles: IP or digital assets can lose value rapidly due to disruption.

Global Perspectives

-

Developed Economies: Wealth is heavily financialized. Most households own financial assets (directly or via pensions). Corporate wealth is largely intangible.

-

Emerging Markets: Wealth still leans on physical assets like land, livestock, and gold. Financial market participation is lower, though mobile banking and fintech are accelerating change.

-

Mixed Economies: Resource-rich countries convert physical wealth (oil, minerals) into financial investments through sovereign funds.

-

Transition Examples: In India, gold and land remain key, but stock investing is growing. In Africa, cattle and farmland still dominate, yet mobile money and crypto adoption show leaps into financial assets.

Conclusion

The evolution of wealth – from nature’s bounty to digital code – highlights humanity’s adaptability. Each era brought a new definition of assets: from tools and land, to factories and stocks, to algorithms and ideas.

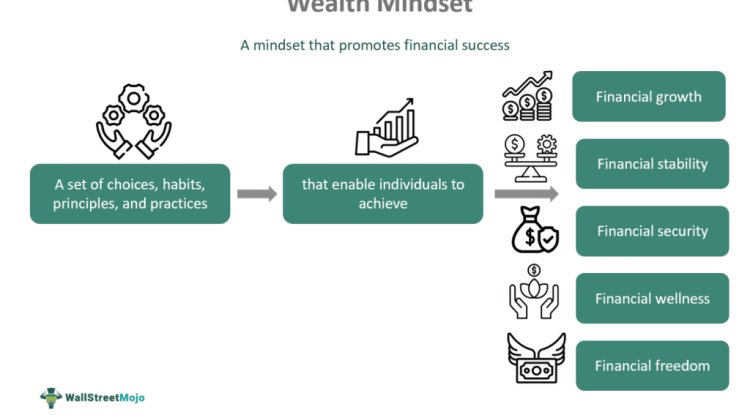

Today, building wealth requires not just assets but also financial literacy and agility. The modern system offers unprecedented opportunities, but also volatility and inequality. A balanced approach – combining physical stability (like real estate), financial growth (stocks, bonds), and intangible creation (skills, IP) – may be the smartest path forward.

Wealth is no longer static. It evolves with technology, knowledge, and adaptability. Those who learn, pivot, and diversify will thrive in this age of intangible assets, just as landowners thrived in the agrarian age and industrialists in the factory era.

What's Your Reaction?