NSSF Crisis in Kenya: Why Rising Deductions Are Shrinking Retirement Savings

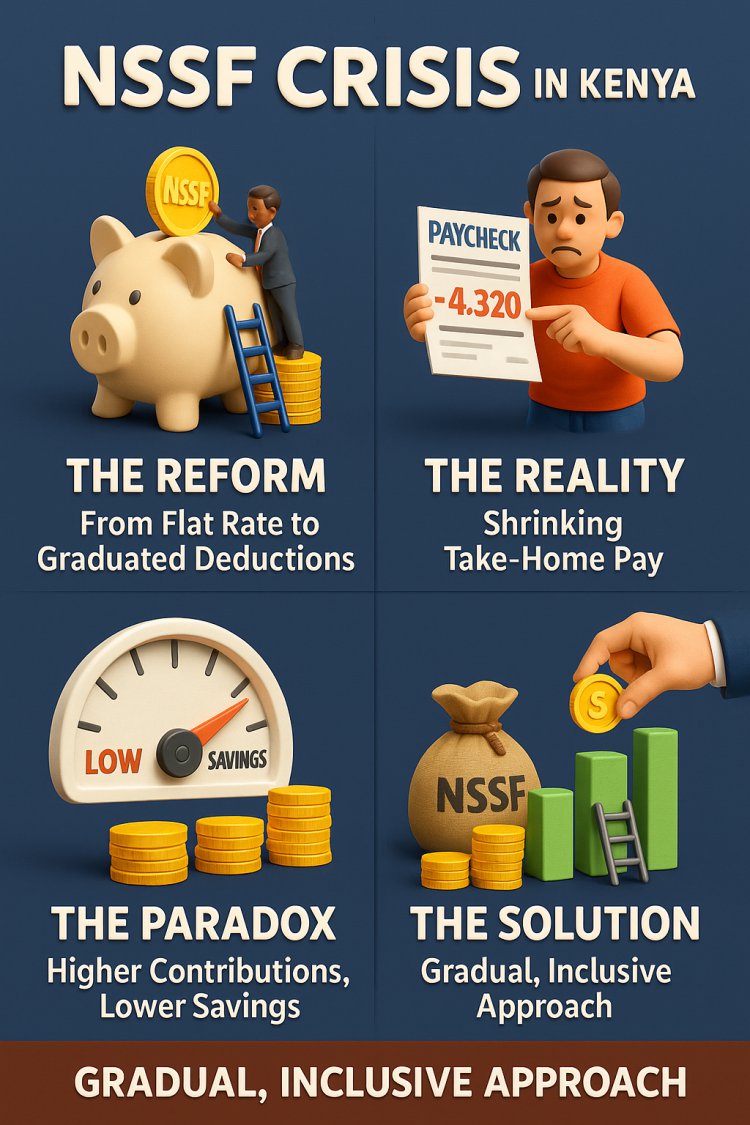

Kenya’s NSSF reforms aimed at boosting retirement savings have backfired. Mandatory deductions of up to Sh4,320 per month have reduced take-home pay, forcing many workers to abandon voluntary savings. Contributions per person are higher, but overall savings have plunged by 47%. Without adjustments, NSSF risks becoming a scheme for the elite instead of a national safety net.

Introduction: A Paradox in Kenya’s Social Security

Kenya’s National Social Security Fund (NSSF) was created to be a cornerstone of retirement protection—a safety net ensuring that after decades of work, citizens could retire with dignity and financial stability. For years, however, it has been underfunded, underutilized, and mistrusted by many workers. Recent reforms aimed at strengthening the fund were meant to change this narrative. By raising monthly contribution rates, the government hoped to channel billions more into NSSF, growing the pool of national savings and providing better retirement benefits in the long run.

On paper, this reform looks like a success. NSSF’s annual collections have surged, more than doubling compared to earlier years. Higher-income workers are now contributing thousands of shillings every month, boosting the fund’s liquidity. Yet beneath this apparent success lies a troubling paradox: the amount Kenyans are actually saving through NSSF has collapsed by nearly half. In just one year, voluntary contributions shrank from Sh1.9 billion to Sh1.0 billion, a staggering 47% decline.

This paradox highlights a deeper truth. Social security cannot be built on compulsion alone. By sharply increasing deductions without considering the financial struggles of ordinary workers, policymakers may have undermined the very foundation of long-term savings. Instead of strengthening retirement security, the reform risks turning NSSF into a scheme only the elite can comfortably afford, leaving millions of Kenyans excluded and vulnerable.

The Reform: From Flat Rate to Graduated Deductions

For decades, NSSF contributions were capped at a flat rate of Sh200 per month. Critics argued this was outdated and insufficient to build meaningful pensions. The government responded by implementing the NSSF Act of 2013, which introduced a graduated contribution scheme tied to income levels.

-

Under the new structure, contributions are based on salary bands, with both employee and employer matching amounts.

-

For higher-income earners, monthly deductions now reach as high as Sh4,320, compared to Sh2,160 previously.

-

Lower-income workers still contribute less, but overall, every Kenyan in formal employment now sees a much larger portion of their salary directed to NSSF.

The government’s stated goal was clear: raise national savings, expand retirement coverage, and bring Kenya closer to international best practices in social security funding. In principle, this goal makes sense. For decades, Kenyans have struggled with low pension savings, with estimates showing that over 80% of the population lacks formal retirement coverage.

But the problem was not simply low contribution rates—it was also low participation. Millions of workers in the informal economy were never part of NSSF to begin with. By focusing on squeezing more out of the existing contributors rather than broadening the base, the reform may have missed the mark.

The Reality on the Ground: Shrinking Take-Home Pay

The first and most immediate effect of the higher deductions has been a reduction in take-home pay. For a worker earning Sh50,000 per month, a Sh4,320 deduction represents nearly 9% of their salary. When combined with other statutory deductions such as PAYE tax, NHIF contributions, and housing levies, many employees are left with far less disposable income than before.

Kenya is already grappling with a high cost of living. Food prices, rent, transport, school fees, and medical expenses consume the bulk of household incomes. Most families live paycheck to paycheck, with little room for discretionary spending or saving. When compulsory deductions rise sharply, workers are forced to adjust. But rather than increasing total savings, many end up reducing or eliminating voluntary contributions to NSSF or other pension schemes just to keep afloat.

This explains why voluntary savings through NSSF have collapsed. Workers who once set aside extra funds for retirement have now cut back, redirecting every shilling toward immediate survival. In some cases, employees may even view NSSF as an additional burden rather than a benefit, eroding confidence in the system.

The Paradox: Higher Contributions, Lower Savings

The paradox is clear. By forcing higher contributions, NSSF has increased the amount collected from individual workers. However, this has discouraged broader participation and reduced voluntary top-ups. The result is that total voluntary savings have fallen dramatically, even as mandatory inflows have risen.

This trend is dangerous for several reasons:

-

Reduced Inclusivity – Instead of attracting more contributors, the fund risks becoming exclusive to higher-paid employees who can absorb the deductions.

-

Weakened Trust – Workers may begin to view NSSF as punitive, reducing voluntary participation and undermining confidence in the system.

-

Short-Term Pain Without Long-Term Gain – While contributions are higher today, many workers may look for ways to withdraw funds early, defeating the purpose of retirement savings.

-

Policy Blind Spots – Policymakers overlooked the reality that forced savings do not automatically translate into long-term security if they reduce households’ ability to meet current needs.

Why the Policy is Backfiring

Several structural factors explain why the policy is backfiring:

1. Economic Strain

The reform was introduced at a time when Kenyans are already under economic pressure. Inflation has eroded purchasing power, wages have not kept pace with rising costs, and unemployment remains high. Forcing higher deductions in such a climate worsens financial insecurity.

2. Focus on Quantity, Not Quality

The government focused on how much money NSSF could collect rather than how many Kenyans could be sustainably included. A social security scheme must balance both.

3. Employer Pushback

Employers are also required to match employee contributions. For businesses, this significantly raises payroll costs, especially for SMEs. Some employers may respond by limiting hiring, freezing wages, or encouraging informal work arrangements that bypass NSSF entirely.

4. Exclusion of Informal Sector

The informal economy makes up nearly 80% of Kenya’s workforce. These workers were largely excluded before, and the new rates have not made NSSF more attractive or accessible to them. Instead of expanding coverage, the reforms have deepened the divide between formal and informal workers.

5. Poor Communication

Many workers do not fully understand how the new deductions benefit them in the long run. Without clear communication, deductions feel like taxes, not investments. This perception undermines confidence in NSSF.

Lessons From the Decline

The 47% drop in voluntary contributions is not just a statistic. It is a warning sign. It tells us that Kenyans are unwilling—or unable—to save at the levels being demanded of them. Policy cannot ignore human behavior and economic constraints.

This decline also reveals a critical truth: retirement security is not only about how much money is collected but also about how many people are able to participate and remain consistent. A national fund that relies on high contributions from a small elite cannot deliver inclusive social security.

The Risk of NSSF Becoming an “Elite Fund”

If the current path continues, NSSF may increasingly serve only a narrow segment of the workforce: well-paid employees in the formal sector. These individuals, while significant, are a minority in Kenya’s labor market. The vast majority of workers—casual laborers, small traders, informal professionals—remain excluded.

This risks creating a two-tier retirement system:

-

A small group with meaningful pensions through NSSF and private schemes.

-

The majority with no formal coverage, relying on family, community, or meager personal savings in old age.

Such inequality defeats the very purpose of a national social security fund, which should be broad-based and inclusive.

What Needs to Change

To realign NSSF with its mission, Kenya needs a more thoughtful approach. Here are several recommendations:

1. Gradual Phasing-In

Instead of sudden jumps in contribution rates, the government should phase in increases more gradually. This allows households and employers to adjust over time.

2. Tiered Contributions

Introduce contribution rates that better reflect income levels. Low-income workers should not be burdened with rates that undermine their ability to meet daily needs.

3. Incentives for Voluntary Saving

Encourage voluntary contributions through tax breaks, matching schemes, or other incentives. Workers must see a clear benefit to saving more.

4. Focus on Informal Sector Inclusion

Innovative solutions are needed to bring informal workers into the system. Mobile platforms, SACCO partnerships, and flexible contribution schedules could help.

5. Transparent Communication

Workers need to see how their contributions grow and what benefits they will receive. Greater transparency will build trust.

6. Employer Engagement

Policies should balance the need for retirement savings with the realities of business costs. Employer incentives may help sustain participation.

Broader Implications for Retirement Security in Kenya

The NSSF crisis is part of a broader challenge: Kenya’s retirement system is fragile and uneven. Private pension schemes cover only a small share of workers. Informal sector savings are inconsistent. Most Kenyans risk entering old age without reliable income, placing pressure on families and the state.

Rethinking NSSF is therefore urgent not just for today’s workers but for the future stability of Kenya’s economy. A country with millions of elderly citizens lacking pensions will face social and fiscal crises down the line.

Conclusion: A Call for Rethinking

The collapse of voluntary savings at NSSF shows that reforms designed without considering economic realities can backfire. Higher deductions may look good on paper, but they are hurting workers in practice. Instead of strengthening retirement security, the current approach risks narrowing participation, weakening confidence, and turning NSSF into a fund for the privileged few.

Kenya needs a retirement policy that is inclusive, gradual, and responsive to the daily struggles of ordinary citizens. Only then can NSSF truly fulfill its mission as a national safety net.

The lesson is clear: savings cannot be forced on people already struggling to survive. Social security must be built on trust, inclusivity, and realistic contributions—otherwise, it risks becoming irrelevant to the very people it was created to protect.

What's Your Reaction?